I'm hoping to make this an annual tradition here at In Contention. It's no secret we have a lot of respect for below-the-line talent around these parts, but it's nice to have a visual way of showing that appreciation. I sat down to write this piece for the first time

last year, taken by the caliber of cinematography we had to bask in throughout the year and, indeed, the awards season. The unusually high number of lensing achievements in 2007 left a slew of images to choose from and it was difficult whittling it down to 10.

This year the challenge was of a different sort. The field was curiously thin. It wasn't that the talent wasn't on display. God knows, a number of the greats were lining up behind the camera this year. But the images weren't as instantly iconic or as viscerally gripping as they were in 2007, which might have left me a bit disappointed on one hand. Then again, it just made searching for my favorites all the more involved and interesting, and I'm happy to offer my findings to you in this space, even if it meant doubling up.

Yes, in one instance (an undeniable one, really), a certain film found two shots popping up on the list, and nearly three. Another film also found itself close to a second mention, but I tried to keep a balance of honesty and fairness in place as much as possible. If a film has two of the year's best shots, it has two of the year's best shots, right?

This year, things are slightly different. Last time around, I got a few arbitrary quotes from lensers throughout the season and plugged them into the piece where they fit best. This year, I sought out the various directors of photography to get their opinions on the specific shots in question. Their insight, as always, makes for a better story and, indeed, more context for the reader. I hope you enjoy reading their thoughts as much as I did collecting them.

So, I look forward to doing this each and every year I'm cranking out copy for your reading pleasure (or displeasure). In my view, it is one of the best ways I can commemorate the technicians that so often find themselves overlooked this time of year.

So let's get on with the list…

#10

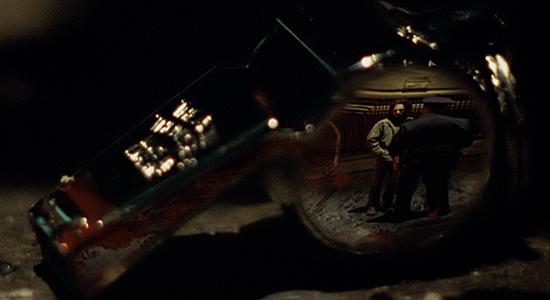

"MILK"

Director of Photography: Harris Savides

It's really simple and it wasn't planned at all. We were shooting the scene and the last shot that night was a close-up of the whistle. Gus and I were talking and we thought it would be great if we saw the whole scene in this whistle, and Gus made it happen in post. They took one of the shots and put it in this shot, the close-up of the whistle we got. I was surprised that it happened at all. But that kind of stuff, especially with Gus, is very on the fly. There's no storyboards.

–Harris Savides

Ask any working cinematographer who the two or three best lensers are in the game, you're likely to hear Harris Savides every single time. In his collaborations with David Fincher, Jonathan Glazer and, prolifically, Gus Van Sant over the years, Savides has amassed a distinguishing visual portfolio that would likely catch the late Stanley Kubrick's eye.

Hopping behind the camera for the fifth time with Van Sant at the helm, Savides brought his distinctive sense of composition to the director's signature creativity yet again. Perhaps one of the more straight-forward of their collaborations, the photography in "Milk" was nonetheless a well-implemented storytelling device for the life of San Francisco politician Harvey Milk.

The shot that stuck out to me when first watching the film might be considered too gimmicky to some, but I couldn't help a crooked smile at the playfulness on display. I was later somewhat disappointed to learn, as the quote above reveals, that the shot was achieved through visual effects, but it wasn't enough to erase the image from my mind: a distressed Milk confronts a police officer following a violent night of gay-bashing in the Castro as a whistle — a plot point raised earlier in the film — lies blood spattered on the ground, reflecting the scene throughout.

#9

"DEFIANCE"

Director of Photography: Eduardo Serra

I like this shot very much as well because you have all that emptiness and Daniel is separated from the rest. When you have all the snow, all the white around, you have reflections everywhere. That creates a mood that's very special. I didn't do anything with this shot other than giving the film a certain look using a specific film stock. There's not much you want to do with lights because you have all this white. I'm always very interested mainly by the storytelling rather than anything else. It's very simple, there's nothing, no bells, no nothing, it's very simple.

–Eduardo Serra

Eduardo Serra cut his teeth on the French cinema of the 1990s. He broke through to North American audiences with Michael Winterbottom's "Jude" and Iain Softley's "The Wings of the Dove," the latter earning him an Oscar nomination, before dazzling popular audiences with Vincent Ward's "What Dreams May Come" and M. Night Shyamalan's "Unbreakable." But most remember him for his gorgeous work on Peter Webber's "Girl with a Pearl Earring" in 2003, which brought him Academy attention for a second time.

Serra has been director Edward Zwick's D.P. of choice for the last couple of years, lensing "Blood Diamond" in 2006 and, most recently, the World War II drama "Defiance." In many ways Serra is a perfect fit for Zwick, who has proven himself quite attentive to the visual splendor of his films (lauded lensers Roger Deakins and John Toll have been frequent collaborators).

Serra's finest work in "Defiance" comes during the film's extended winter sequence, a detrimental time for the Bielski brothers and their patchwork community seeking asylum in the forest of Belarus in the early 1940s. That detriment is paradoxically captured in the most beautiful blue-white hues as snow (both fake and real) covers the scenery. But the shot that stuck out to me was both an interesting (and heartbreaking) plot point and the moment that really snapped me to the attention deservingly paid to Serra's photography.

#8

"REVOLUTIONARY ROAD"

Director of Photography: Roger Deakins

You kind of work the shot by what's demanded by the story. The front of the shot is just Frank coming in the door and the exterior of the porch light that sort of rims him as he walks in. It was an aesthetic reason because it helps set the mood of the shot. We wanted this pool of warm light, sort of coming through this dark room and not knowing what you were going to expect. It was about capturing the surprise of Frank seeing that scene and that mixed emotion. And it wasn't lit entirely by the candles. I asked the art department to make a cake that was big enough that I could hide a little gag light behind it.

–Roger Deakins

There are few lensers as salty, candid and talented as Roger Deakins, the most Oscar-nominated cinematographer of all time without a statuette to his credit. He has worked with the greats, from Martin Scorsese to frequent collaborators the Coen brothers. This year he sat behind the camera on three major productions: John Patrick Shanley's "Doubt," Stephen Daldry's "The Reader" and Sam Mendes's "Revolutionary Road."

"Road" is littered with an embarrassment of visual riches, an assemblage it seems only Deakins could deliver with such consistency. But it was surprisingly difficult to settle on one frame that really stuck out, because unlike many of his works, the film is more memorable for its overall visual atmosphere than it is for this shot or that. But I eventually settled on an eerie image, the camera tracking with Leonardo DiCaprio's Frank Wheeler after a day of infidelity, through the darkness to reveal his family, lit by birthday cake candlight to wish him a happy birthday. The beauty and moodiness of the shot mixes together with the subtext of his recent actions in an unsettling way that was certainly intentional.

Deakins has filled in wonderfully as Mendes's D.P. of choice as of late, stepping into the massive shoes of lensing legend Conrad L. Hall. But Deakins, who was close friends with Hall before Hall's death in 2004, says he considers it an incredible honor, for obvious reasons. Most notable, however, is Mendes's talent for utilyzing the best in the business.

#7

"SLUMDOG MILLIONAIRE"

Director of Photography: Anthony Dod Mantle

I like to experiment, but I only ever experiment because of the story. We thought bringing him really close in the foreground would be good to create that distance between the two boys and create that dramatic comment. One of them is thinking about something else and the other is simply thinking about surviving and moving on. It's a sad image too because you can't help the connotation that these boys have lost their mom, you know. And those things don't get storyboarded. Generally speaking when you're working with Danny, every shot feels as important as every other one. And that shot is an example of the way we work . He'd have an idea for a picture and I'm there to help him as a visually trained composer of images — that's my job.

–Anthony Dod Mantle

Anthony Dod Mantle made his name alongside Thomas Vinterberg and Lars Von Trier during the Dogme movement of the late-1990s. The naturalism at the forefront of Dogme's dogma nonetheless finds itself at incredible odds with the cinematic sensibilities of director Danny Boyle, who has worked with Mantle on three films since 2003′s "28 Days Later."

Still, Mantle has found a way to let his background influence his work with filmmakers like Boyle and Kevin Macdonald in the most pleasantly surprising of ways, and such was the case on "Slumdog Millionaire," perhaps the most visually dynamic piece of cinema to be released in 2008.

Much like Deakins's work on "Revolutionary Road," Mantle's work here doesn't easily allow for one or two easily remembered images. It is a construction of ideas that pop with life, camera innovations that are astounding and viscerally effective, but more across the board than selectively so. I went back and forth on which image to choose, and I always came back to the same frame, young Jamal in the foreground, lost in thought and heartbreak as a young Salim looks toward renewed life in the background. The moment comes during the film's energetic train montage sequence and really, I don't think I could add more than Mantle has in the quote above, so I'll leave it at that.

#6

"THE WRESTLER"

Director of Photography: Maryse Alberti

The first time I spoke to Darren, it was very clear that the inspiration for the visuals of the film was in the work of the Dardenne brothers, who directed "Rosetta" and "L'Enfant." That first shot was going to be much more complicated, a low, hand-held tracking shot that was going to move in on Mickey and turn around and start to discover his face. We tried it and Darren decided it was much too complicated. We decided to leave the camera in the back of the room with Mickey very small in the frame with his back to us and I think that right away it established the isolation of the character.

–Maryse Alberti

When director Darren Aronofsky went back to the drawing board on "The Wrestler," he shrugged off the sleekness of "The Fountain" and the indie-chic of "Pi" and "Requiem for a Dream" in favor of a much more naturalistic visual approach. Hiring documentary lenser Maryse Alberti was a smart move in the realignment of his career and his newfound passion for performance.

"The Wrestler" is filmed in such a way as to invite the viewer into the life of Randy "The Ram" Robinson. While Mickey Rourke is laying bare his soul on the screen, Aronofsky and Alberti are meeting him half-way with an affectionate portrait and a sense of realism that might remind the viewer of one of the many examples of cinematic non-fiction Alberti has filmed in her time. The shots linger and observe, omniscient but intimate, obliterating the notion that a camera is even there.

The most powerful image is probably the opening frame, one packed with as much subtly as it is blatant thematic comment. That it was a fall-back plan of sorts, and never prepared as such, is somewhat shocking considering the artistic merit it exhibits, but such is the essence of filmmaking, cooking imagery on the fly and tapping into the hidden truths that trimmed production fat can reveal.

Before digging into the top five today, I thought I would give a shout out to the images that almost made the cut, and there were a few. For instance, who can forget the fateful shot of Harvey Milk ascending the stairs of San Francisco's City Hall as Dan White stalks the corridors in the distance? Similarly, how about the image of White from behind as he psyches himself into assassinating his fellow politician?

Meanwhile, there was an array of images to choose from in "The Dark Knight," certainly too many to name here. As beloved as the image of Heath Ledger's Joker is, breathing in his freedom and tearing off into the night in a Gotham patrol car, I chalk that up to performance as much as if not more than Wally Pfister's work behind the camera. But the iconography of James Gordon standing, arms crossed in front of the Bat signal was a difficult one for me to snub (for reasons you'll find out after the jump).

"Let the Right One In" will show up on today's list, but one other image that came very close to making the cut for me was that of Eli's victim bursting into flames on a hospital bed once exposed to sunlight streaming in through the window. And though Maryse Alberti's work on "The Wrestler" has already been represented, I was always tickled by the creativity of The Ram's walk through the bowels of a supermarket deli, mirroring his walk to the ring.

Finally, Danny Boyle's "Slumdog Millionaire" is loaded with wonderful cinematography. The image I chose yesterday had personal value, but I also loved the long shot of young Jamal and young Salim on the roof of a train to start the film's exciting montage, as well as the three-shot overhead view of the Mumbai slums during the film's opening sequence.

This is to say nothing of the work from fine lensers on films that just didn't make the cut for whatever reason, but were nonetheless wonderful examples of cinematography this year. "The Fall" (Colin Watkinson), "Gomorrah" (Marco Onorato), "The Reader" (Roger Deakins and Chris Menges) and "Vicky Cristina Barcelona" (Javier Aguirresarobe) are just a few examples.

But enough of the also-rans, right? Let's get on with the real show: the five best shots of 2008…

#5

"THE DARK KNIGHT"

Director of Photography: Wally Pfister

Chris and I had long conversations discussing the best way to film this scene. This is the last we see of the Joker in the film and sadly one of the last days we were ever to work with Heath. We went back and forth trying to decide whether to leave him upside down in the frame for the whole scene or rotate the camera and have him right-side up and we did not make our decision until that day. Chris felt that, as long as we showed the camera rotation, and let the audience "in," that the scene would play better with the Joker's face upright. The end result is, of course, this eerie right-side-up image that defies gravity. We kept the illusion of the police helicopter flying around to motivate my overexposed blue, flickering light on the Joker's face throughout.

–Wally Pfister

Christopher Nolan's "The Dark Knight" is perhaps the most photographically sound film of 2008. To say nothing of the breathtaking innovations Nolan and D.P. Wally Pfister ushered to the mainstream by tinkering with IMAX technology, the film is composed, moment-for-moment, with the utmost expertise and thematic intent. Choosing just one image would bee a fool's errand. I had to go with two.

Of course, as mentioned in the lede, there are numerous frames to choose from. Click here, here, here and here for just a couple more examples. My own favorite image might be this one, but I had to answer to a higher calling for the purposes of this list, shots that truly said something, capturing iconography and creative liberation all at once, regardless of my fanboy glee over seeing images from my favorite graphic novels duplicated on the screen.

For the first of two "Dark Knight" images selected, I chose a shot that brings an extra element of cinematic uniqueness to Nolan's already classic vision of the character: the Joker, finally in the Batman's clutches, suspended high above Gotham as he taunts his archenemy further. The off-screen pain of the line "You and I are destined to do this forever" will always sting, but for Pfister and Nolan's part, Heath Ledger's final moments in the film are captured in an unsettling manner worthy of the actor's maniacal creation.

#4

"THE CURIOUS CASE OF BENJAMIN BUTTON"

Director of Photography: Claudio Miranda

David likes being able to roll instantly and he likes the convenience of HD, but of all the shots that was probably one of the easiest ones of the whole movie. It was just trying to be as naturalistic as possible. I get drawn to it more emotionally, because it's not busy with light or camera movement at all. There's no real equipment on that shot. There's just a camera and a couple of actors out there and we were blessed by a little bit of overcast and there you go. It was one of those happy accidents. And it just seemed to have a great mood to it, the tree kind of pushed in on the side with this nice bell shape. Everyone has their favorite shots but a lot of people react to that one.

–Claudio Miranda

Whether or not the Academy's cinematography branch finally warms up to digital photography hardly matters in the face of the technology's accelerated proliferation in the film industry. But while we've seen nice work from lensers like Dion Beebe and Dean Semler in that vein in the past, I don't think anyone has really conveyed the potential for gorgeous digital imagery the way Claudio Miranda did on David Fincher's "The Curious Case of Benjamin Button."

Miranda has been a part of Fincher's creative ensemble for a number of years. He worked on "Seven," "The Game," "Fight Club" and "Zodiac" before taking the helm of a Fincher camera department for the first time this year. However, he cut his teeth as a lighting technician, which goes a long way toward explaining his wonderful eye for visual ambiance.

"Button" is packed with beautiful imagery, but it can be difficult at times to discern what is digitally enhanced. The red dress sequence that is so beloved, for instance, wouldn't have had the same effect if Fincher hadn't spiked the red in post. But the shot that always causes me to gasp a little everytime I see the film is the one you see here, startling on an emotional level but carrying with it an eerie weight that sums up the film so well atmospherically.

#3

"HUNGER"

Director of Photography: Sean Bobbitt

It is an interesting shot in that it sort of highlights the working relationship between myself and Steve McQueen. He said it was as if the camera was a balloon bouncing around the room, always looking at Michael. There was no visual reference that he could think of but he had a gut feeling that there was something about that movement of the camera. It highlights Steve's creativity because he's coming from the world of art. We had several discussions about how you get a camera to move like that, coming up with all sorts of rigs — including large balloons — none of which were really practical. As we were getting more into the shoot, the birds started to grow in importance, and for Steve it was suddenly clear that it wasn't a balloon, it was a bird, and the bird represented Bobby Sands' soul, trying to escape this room.

–Sean Bobbitt

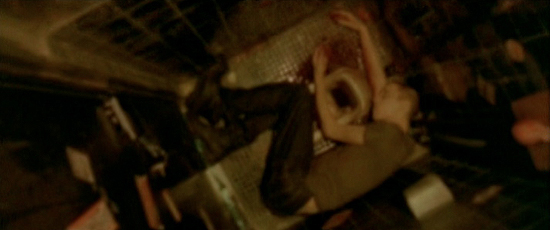

Steve McQueen's "Hunger" is a visual masterpiece, loaded with captivating images sprung from the mind of a contemporary artist in this, his first feature film. One could talk all day about the virtues of the film's narrative structure, a broken string of moments that catches its stride in an extended glimpse of hunger striker Bobby Sands (played brilliantly by Michael Fassbender) in his final days of incarceration at HM Maze Prison outside of Belfast.

Sean Bobbitt has spent much of his time in the world of television as of late, but it seems a collaboration with McQueen was all it took to unleash a ferocious sense of creativity in the lenser. He captures the Maze with a number of clever and thematically potent angles and hues, equally effective with elaborate camera movement and the stillness of visual commentary.

The shot that stuck out in my mind comes late in the film, perhaps the most unusual of the numerous memorable images on display. The camera hovers above Fassbender as he goes into a series of convulsions, forgoing whatever fluids might have remained in his stomach. It then pushes in swiftly on the actor as the viewer hears the sound of bird wings flapping, then out again, repeating the movement a number of times before resting in a somewhat defeated manner. I do it no justice here; the movement is excellently explained by Bobbitt above.

#2

"THE DARK KNIGHT"

Director of Photography: Wally Pfister

The Battersea Power Station has such a wonderful history and was perfectly suited for our story. There are very few locations where you can find that kind of scale. Chris really likes these iconic Batman images (the helicopter shot of Batman on top of the tall building is another) and usually uses them in very powerful, emotional moments in the film. All that weight was presented on a massive, eight-story screen when viewed at an IMAX theater. I was quite pleased with the duality of the color palette, the blue of the dawn light mixed with the warm, orange of the fire light. We decided to shoot this as a dawn scene, as it allowed us to see much more of the destroyed Battersea interior than we would have had it been a night scene.

–Wally Pfister

As Pfister notes in his comment above, one of the things Christopher Nolan has nailed with his Batman franchise is the iconic imagery of the character. The first shot that really put fanboys on the edge of their seats in 2005 was that sweeping helicopter shot of the Caped Crusader perched atop a Chicago skyscraper in "Batman Begins." At the time, comic artist Jim Lee called it his favorite image from the series's reboot.

Translating that sense of iconography to IMAX photography was just one more way of adding a sense of majesty to the character and, indeed, lending a greater sense of importance and urgency to the events of "The Dark Knight." And there was ultimately one image that came to define the film for me, both in this way and in a general sense overall. The choice was simple.

A battered but unbroken Batman stands on a pile of blown-out rubble, fires blazing all about him, looking down with the heavy heart of a shadowed hero. Using the Battersea Power Station in South London only amplifies the grandiosity of the image, but what is most startling is that, though it seems instantly iconic, there is no real reference for the composition, no frame in a comic book to inspire the image. It was born out of Nolan and Pfister's creativity and dedication to capturing the essence of a character that has struggled to find that identification on the screen for decades.

#1

"LET THE RIGHT ONE IN"

Director of Photography: Hoyte Van Hoytema

This shot can be seen as a compressed example of how we tried to treat the story throughout the film. It pretty much followed the ideas Tomas and I had about how to show cruelty, action and supernatural elements and where to put focus. We wanted to be close on Oscar and the way he experiences the situation, as well as have a platform to tell everything that happens in one shot. I am not sure if it is the most "pretty" frame of the film, but it was very exciting to try to unravel and solve the puzzle of all present elements in this shot, technically, as well as emotionally. I am very proud of Tomas and the way he dared to go with a climax that is so violent, but restrained and subtle at the same time.

–Hoyte Van Hoytema

Tomas Alfredson's "Let the Right One In" has been considered one of the year's best films in many quarters. It is a burst of creativity and ideas that stretches far beyond the realm of the visual. I think vampire chic has enjoyed its 15 minutes. And it wasn't working anyway. When Hollywood wasn't raping and pillaging the work of Richard Matheson it was copying and pasting the work of Stephanie Meyers, both times to box office success of course. And who can forgive the many faults of television's "True Blood?"

Along came Alfredson and his brilliant D.P. Hoyte Van Hoytema and, hopefully, they've changed all that. Who knows how wretched the American remake of "Let the Right One In" will be, but that a film this dynamic and artistically exciting will serve as a jumping off point certainly nurtures a sense of hope. Then again, fool me once…

Like many of the films on my list, this one is scattered with memorable images. The sound work should be noticed as much as Hoytema's work behind the camera, by the way, but we're focused on cinematography here, and there was really only one image worth considering, not merely as the best frame from the film but as the year's single greatest shot. Young Oscar (Kåre Hedebrant) is held under water by a pack of bullies who've haunted him throughout the film. At first the audience isn't quite sure what is happening above the surface, but as the bloody pieces begin to fall into place, we know. And we're dazzled. This is the moment that finally made the film click in my head as one of the year's best. I can't imagine that I'm alone.

And that's a wrap! This is, without a doubt, the feature I look forward to writing each year more than any other. Again, I hope you all have enjoyed the list as much as I did compiling it. These were my 10, but feel free to cut loose with your picks for the year's best shots in the comments section below.

The top 10 shots of 2008