In my last post, I revealed my debt to Chris Vogler and where I diverge from him on Character Arc. Here I outline a new character-driven Hero's Emotional Journey that might help dispel notions that this amazing paradigm doesn't apply to female protagonists, intimate dramas or romantic comedies.

The Hero's Journey outlined in Chris Vogler's book The Writer's Journey is the single most important thing I've learned as a screenwriter. It totally transformed my understanding of story and I think every screenwriter should read it. However, there is some resistance to the Hero's Journey and I can understand why misconceptions have arisen.

Myths about the Hero's Journey

There are a couple of complaints I commonly hear about the Hero's Journey. One is that is only applies to male protagonists. The other is that it might work if you're developing a Star Wars sequel but not if you're writing an intimate drama. I've never laboured under either of these misconceptions – hell, I write romantic comedies – but it's not hard to see why people might form these opinions.

Offputting warrior metaphors

The Hero's Journey is just as applicable to female protagonists like Juno as it is to "warriors" like Luke Skywalker or Indiana Jones.

Vogler stands on the shoulders of mythological guru, Joseph Campbell, so it's not surprising that he uses terms like "Call to adventure", "Supreme Ordeal" and "Approach to the Inmost Cave" to define the 12 steps of his Hero's Journey. However, it's easy to see why these warrior metaphors might lead people to believe the paradigm would only be appropriate for testosterone-addled protagonists on a quest to find the Holy Grail (or a misplaced groom).

Plot-driven rather than character-driven

One of the reasons I've always loved the Hero's Journey is that the transformation of the protagonist is bound into the paradigm. If you understand the Hero's Journey, and apply its principles, it's impossible not to have your hero altered by their odyssey. And the emotional power of a film depends almost entirely on the size (and the credibility) of that transformation. However, if you were put off by the terminology, it's easy to understand why you might walk away thinking that the Hero's Journey valued plot over character.

Where I disagree with Vogler on character arc

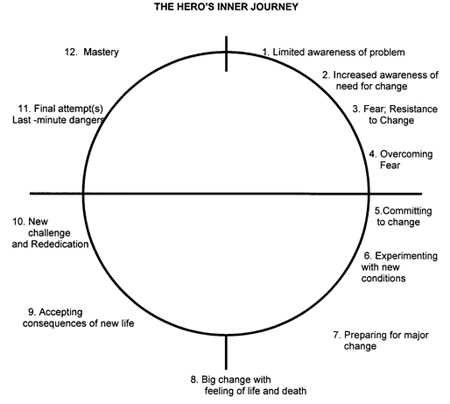

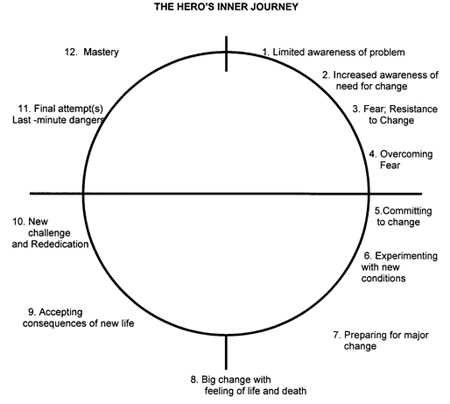

This is Chris Vogler's view of the character arc in the Hero's Journey. He advocates the protagonist changes from the beginning. I think it's preferable to delay addressing the flaw until Step 8 The Ordeal.

In that last post, I detailed why I disagree with Vogler on character arc. In summary, Chris says that the character should be evolving from the beginning of the story, whereas in most of the films I love this doesn't happen. The hero doesn't address their fundamental character flaw until they're forced to at Step 8 The Ordeal – around the midpoint of Act 2. I prefer to delay this transformation because flawed characters tend to be more interesting (and funnier), and postponing the change leads to much greater conflict and emotion in that confrontation scene.

A new character-driven Hero's Emotional Journey

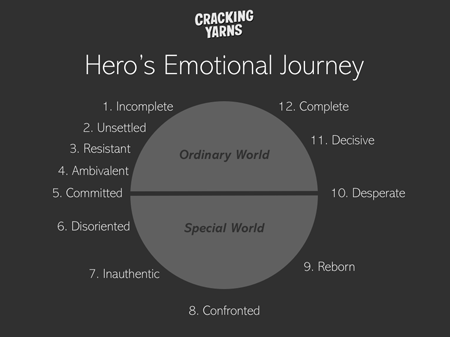

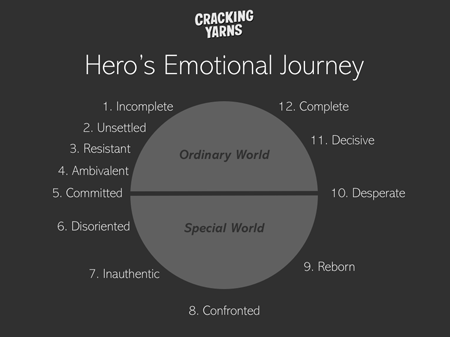

Over the last couple of years, whenever I teach my Introduction to Screenwriting course, I have been augmenting the 12 steps of the Hero's external journey with what I consider to be the 12 steps of the Hero's Emotional Journey.

I think this Emotional Journey helps dispel common misconceptions about the Vogler paradigm and hopefully will allow a much broader range of writers to benefit from the amazing insights of Joseph Campbell.

In fact, to emphasise the point that the Hero's Journey is equally applicable to dramas and romantic comedies, I generally only show one clip from an action-adventure film – and that's the scene from Raiders of the Lost Ark where Marion kisses Indiana.

So here they are …

- Incomplete (Ordinary World)

- Unsettled (Call to Adventure)

- Resistant (Refusal of the Call)

- Ambivalent (Meeting with the Mentor)

- Committed (Crossing the first threshold)

- Disoriented (Tests, Allies & Enemies)

- Inauthentic (The Approach)

- Confronted (The Ordeal)

- Reborn (The Reward)

- Desperate (Road Back)

- Decisive (Resurrection)

- Complete (Return with the Elixir)

Let's explore this new character-driven Hero's Journey in more detail …

Step 1: Incomplete (Ordinary World)

The incompleteness of the Hero will generally have two dimensions: something they're aware of, and something of which they're entirely oblivious.

Bridget Jones thinks she's "incomplete" because she doesn't have a bloke but her real problem is her superficialty.

The incompleteness of which the hero might be aware will generally be a "Want". They're not happy with their lives and they're convinced that getting this thing will fix it.

Miles in Sideways wants to get his semi-autobiographical novel published. Thelma wants to spend a weekend away from her dorky husband with gal pal, Louise. And, as Bridget Jones (Renee Zellweger) sculls wine, watches Frasier and sings "All by myself", you get the strong sense that what she thinks is missing from her life is a fella.

However, while it might be important for the Hero's external journey to establish this incompleteness of which they're aware, it is at least as important to make your audience aware of an inadequacy of which they will almost certainly be unaware: their flaw.

If we don't establish the character failing of the hero – or we don't start them off at a sufficiently low point – the transformation isn't going to deliver any emotional power in the 3rd act.

The climax of Dead Poets Society has a 17-year old schoolboy (Ethan Hawke) standing on a desk and saying "Oh, captain, my captain". How can that possibly move us in the way it does? Because the writer, Tom Schulman, makes Todd's flaw abundantly clear in the Ordinary World sequence.

In Casablanca, Rick (Humphrey Bogart) says "I stick my neck out for no-one", in Moonstruck, Loretta (Cher) is going to marry a man she doesn't love, and in Tootsie, Michael Dorsey (Dustin Hoffman) is not only impossible to work with, he is insincere with woman. All of these great films build their narrative foundation by establishing in the first very first sequence of the film, that the hero is "incomplete".

Step 2: Unsettled (Call to Adventure)

In Winter's Bone, Ree's "adventure" is to find her loser, crank-dealing father or lose her home.

I'm comfortable with the term "Call to adventure" and I use it rather than "inciting incident" but that word "adventure" might discourage writers of dramas from thinking that the Hero's Journey has something to offer them. This "adventure" doesn't have to involve guns, high-speed chases or some mystical medieval text. It can just be a problem or an opportunity.

Like in Winter's Bone, for example. Ree (Jennifer Lawrence) needs to track down her crack-merchant father for the rent money, or she, her younger siblings and incapacitated mother will lose their house.

The emotional effect of this Call on the protagonist will depend on whether they want this adventure or not. Indiana in Raiders of the Lost Ark, Ned (William Hurt) in Body Heat and Olive (Abigail Breslin) in Little Miss Sunshine are all thrilled to get the call so they'll be excited.

But, more often, the Hero doesn't want the call.

Bertie (Colin Firth) in The King's Speech is resistant to the unusual techniques, not to mention the impertinent manner, of Logue (Geoffrey Rush); in Toy Story, Woodie hardly welcomes Buzz Lightyear with open arms; and Juno (Ellen Page) isn't thinking about the miracle of creation when her third pregnancy test confirms the positive reading of the previous two. If the hero doesn't want the call, they're going to be disturbed at least, and quite possibly entirely mortified.

Whether the hero wants the call or not, it's fair to say that in either case they're going to be "unsettled". Suddenly their world just isn't the same any longer.

Step 3: Resistant (Refusal of the Call)

It needn't be the hero who is "resistant". In The Social Network, it's Zuckerberg's buddy Eduardo who questions the wisdom of comparing Harvard women to farm animals.

No surprises here. In the Refusal of the Call sequence, the Hero – or those around them – are going to be resisting the invitation to adventure.

If the hero doesn't want the call, they might try to rationalise their refusal by saying they can't afford to go, they don't have the time, that this person is totally wrong for them, that it's impossible or crazy, but basically they're just afraid. And the audience loves that because fear is something that we all understand.

Luke Skywalker is too busy doing chores to save the Rebel Alliance, Bridget Jones is too superficial to appreciate the charms of Mark Darcy (Colin Firth) and Richard (Greg Kinnear) would rather stay at home and preach about his 9-step Refuse-to-Lose program than take his daughter to Redondo Beach for the finals of Little Miss Sunshine.

If the hero does want the call, others will express the fear for them. Eduardo in The Social Network, the hero's sister in Lars and the Real Girl and Zack's alcoholic whore-chasing father in An Officer and a Gentleman all express reservations about what the hero is about to do.

But, regardless of whether the hero wants the call or not, the emotion that needs to be conveyed to the audience at this stage of the Journey is "resistance".

Step 4: Ambivalent (Meeting with the Mentor)

The Meeting with the Mentor is one of the most misunderstood phases of the Hero's Journey. In some films, yes, the hero does meet with a Mentor figure at this point. Obi Wan in Star and Mr Keating (Robin Williams) in Dead Poets Society are classic, older and wiser mentor archetypes who help their novitiates overcome their fears to go on the journey.

In Moonstruck, the "ambivalence" is expressed by father Cosmo, who says Loretta shouldn't marry the "idiot" Johnny Cammareri, and mother Rose who thinks she's wise to marry a man she likes rather than loves.

But the Hero isn't always getting encouragement from an avuncular sage in this sequence so I think the terminology can be misleading.

For me, a better way of thinking about this phase is to see it as a time where the audience hears the evidence for and against going on the journey. If the hero wants the call, we'll be hearing why they should ignore it. If the hero doesn't want the call, we'll be hearing why they should honour it.

In The King's Speech, Bertie doesn't want to work with this weird Antipodean speech therapist. But having been reminded by his father, King George V, of the importance of broadcasting for the modern monarch – and having been given no help or sympathy in dealing with that – Bertie is forced to reconsider Logue over there in left field.

In Tootsie, Michael Dorsey has no desire to dress up as a woman to get work as an actor. But after his agent tells him that no-one will hire him because he's too much trouble, he decides to audition for the part his girlfriend, Sandy, missed out on.

In Moonstruck, Loretta's father, Cosmo, says she would be crazy to marry Johnny Cammareri whereas her mother, Rose asks her, "Do you love him, Loretta?".

"Oh, no, Ma".

"Good. Because when you love them, they drive you crazy – because they can."

We've heard two opposing points of view from characters whose grey hair suggests they're mentors, but only one of them can be right. The story will "prove" to us that it's Cosmo, for all his failings, whose advice is closer to the mark.

Don't get hung up on this mentor thing. For credibility reasons, the hero will often be confronted with some sort of authority figure in this sequence. But, if you think about it in terms of an "ambivalence" – of presenting the reasons for going vs the reasons for staying – I think you'll find the appropriate scenes for this stage of the journey.

Step 5: Committed (Crossing the First Threshold)

In the previous sequence, the hero weighed up their options. Now, in this last phase of Act 1, they finally commit to the Journey.

In Star Wars, Luke takes up the challenge thrown down by Obi Wan after discovering his Aunt and Uncle have been murdered.

In the ensemble Little Miss Sunshine, Dwayne only commits to join the trip to Redondo Beach after he gets clearance to apply for flight school.

In Little Miss Sunshine, Dwayne agrees to join the trip to Redondo Beach after his mother tells him she will let him apply to flight school.

In The King's Speech, Bertie listens to the phonograph recording he had previously viewed with derision and is amazed to hear himself speak for the first time without a stammer – making him think that perhaps this Logue character might know what he's on about after all.

Sometimes the hero wants to commit to the journey but they need to convince a Threshold Guardian to let them go on the "adventure". Michael Dorsey desperately needs this job on a daytime soap – even if it means dressing up as Dorothy Michaels – but first he's got to convince the misogynistic director, Ron.

Some protagonists, like Roger Thornhill (Cary Grant) in North by Northwest, don't have a whole lot of choice about going on the adventure.

And sometimes, the hero doesn't really get to decide whether they go on the journey. In North by Northwest, Roger Thornhill (Cary Grant) has no choice but to go on the run and try to clear his name after he's wrongly believed to have killed a delegate at the United Nations.

Similarly, in Groundhog Day, a visit to an out-of-his-depth psychiatrist in Punxsutawney convinces Phil Connors that his problem is not in his head and he must make the best of a bad situation.

Whether the hero is thrilled about it or not, after step 5 of the Hero's Journey, the hero is "committed" to tackling the goal, problem or opportunity with which they've been presented.

Step 6: Disoriented (Tests, Allies & Enemies)

Logue disorients the Duke of York by forcing him to come to his rooms and by impertinently calling him "Bertie".

This step of the Hero's Journey is quite a mouthful, but it's one of the simpler stages to understand. Remember how scary that first day at school was for you when you were 5 or 6? In this first sequence of Act 2, your hero is similarly disoriented.

In their Ordinary World, the hero might have been "incomplete", and they might not have been entirely happy, but at least everything was familiar. Now, as soon as they begin to pursue their goal or fix their problem, their world is turned upside down.

The hero can be forced to deal with changes in terrain, as Bertie is in The King's Speech when he's forced to leave the familiarity and safety of his palace and come to Logue's unusual professional rooms.

The protagonist will often have to go through a change of appearance, as Zack does when he gets his locks shorn in An Officer and a Gentleman.

Different rules might exist in this Special World, as they do in Groundhog Day, or Yes man, where suddenly he has to say yes to any proposal, including a geriatric neighbour's excessively generous method of thanking him for helping her around the house.

Michael Dorsey (Dustin Hoffman) "tests" his Dorothy Michaels disguise on agent, George Field (Sydney Pollack).

Their powers might be different, as they are in Bruce Almighty.

As a screenwriter, you're always looking for conflict, so you'll often want to challenge your disoriented Hero with some sort of "test".

In Tootsie, this happens when Michael goes to the Russian Tea Rooms and tests out his Dorothy disguise on his agent. This not only gives us a good laugh at George's expense, it satisfies an important credibility question: if his agent can't see that it's Michael when he's less than a metre away, Dorothy is ready to fool the American viewing public.

In Meet the Parents, Greg (Ben Stiller) is subjected to a lie detector test by his father-in-law from hell (Robert DeNiro).

In Little Miss Sunshine, the test happens when the clutch gives out on their Kombi and threatens to end their trip when it's only just begun. But, this still dysfunctional family combine to jump-start the car, solving the immediate problem, and beginning their healing process.

You need to be careful with this test that you leave yourself room to escalate the tests at the Ordeal and Resurrection (or Climax). So in Groundhog Day, when Phil Connors drives along the railway tracks, he pulls off at the last minute. Later, he's going to push the Punxsutawney envelope a little more

In One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, R.P. McMurphy takes a shine to stammering Billy Bebbit and an instant dislike to Nurse Ratched (the hair can't have helped).

But, possibly the best way to disorient the hero is by having them try to work out who they can trust and who they should be wary of in this new world – again just like you did at school.

In One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, R. P. McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) quickly bonds with Martini (Danny Devito) and works out that Nurse Ratched is public enemy number one. The Chief is initially impenetrable but he falls into the archetypal category of a Shapeshifter: he doesn't appear to be an ally, but ultimately he's going to be the go-to guy.

Shapeshifters are particularly useful in thrillers and film noir because they disorient the audience, forcing them to engage with exactly the same question the hero is grappling: is this character friend or foe?

Again, don't get hung up on the terminology. If you just think about your hero as being "disoriented", you'll be alive to the wonderful comedic and dramatic possibilities of this first sequence of Act 2.

Step 7: Inauthentic (The Approach)

This is a tricky sequence to nail in terms of the emotional journey of the Hero.

You could consider them to be "amiable", given that this is often where friendships are forged. For example, in The King's Speech this is where Bertie opens up to Logue after his father's death about the mistreatment he suffered at the hands of his nanny and his brother.

You could consider them to be "amorous", given that this is where many love interests are introduced. For example, in Witness, this is where John Book (Harrison Ford) and Rachel Lapp (Kelly McGillis) dance in the barn in a scene dripping with sexual subtext.

Phil Connors in "inauthentic" mode with Nancy.

So, why have I characterised it as "inauthentic"? Because in the next sequence, The Ordeal, you're going to confront your hero with their flaw, so in this sequence I think it's a good idea to remind the audience of exactly what the hero's character failing is.

One of the best examples of this is Groundhog Day, where Phil beds – and proposes to – local Punxsutawney girl and Lincoln High grad, Nancy. At this stage, he's not interested in using his special powers to help anyone. Why? Because his flaw is that he's selfish. So in this sequence we see him being entirely "inauthentic".

When I say "inauthentic", I don't just mean that he's saying things that he doesn't feel. I mean that there is a gap between how the character presents to the world – their "identity" – and who they really are – their "essence".

In The King's Speech, even though Bertie is being open with Logue in this sequence where their friendship is forged, there is still a yawning gap between how Bertie presents to the world and who he really is.

His identity is that he's the bumbling, stammering younger brother of the dashing heir to the throne, David, but in truth Bertie has qualities that will serve the nation better than that flibbertigibbit. But he won't get to offer those abilities, or be comfortable with himself, unless he has the courage to find his voice.

Yes, the Approach sequence can involve rehearsal and reconnaissance and romance, but if you want to write an emotionally engaging film, I'd encourage you to consider how to reveal that the character is being "inauthentic". If you do, you'll be perfectly placed to exploit the drama of this next sequence.

Step 8: Confronted (The Ordeal)

Vogler calls this stage "The Supreme Ordeal" but I've known students to form the impression that this means it's the moment of greatest drama in the story. That's not what Chris intended so I just refer to it as "The Ordeal".

Ennis (Heath Ledger) is "confronted" in Brokeback Mountain when Jack (Jake Gyllenhall) refuses to accept his continued duplicity.

However, when I teach the Hero's Journey, it's the clips from this stage of the journey that produce the greatest emotion in the class. And in an earlier post on the midpoint, I've written at length on why this is such an important stage in the character arc. In summary, it's where the hero is "confronted" with their flaw.

Up until now, the hero won't have addressed their flaw because they haven't had to. Not only have they done nothing about it but they've possibly been exploiting it. But here they reach an impasse because here someone – often an antagonist or mentor/antagonist – holds a mirror up to the hero and says, "Here you go, pal, take a good long, hard look at yourself. Not pretty, is it?!?".

This is where, in the great films, the inauthentic identity the hero has been presenting to the world will crack and crumble away, revealing for the first time their true essence.

In Tootsie, it's where Julie (Jessica Lange) throws a glass of water in Michael's face – because he's using the same inauthentic patter on her that he was in the opening scenes.

In Groundhog Day, Phil is using the same inauthentic approach on Rita that worked on Nancy, but every time he's on the verge of the Promised Land, she gives him a good slap.

In Brokeback Mountain, Jack (Jake Gyllenhall) finally calls Ennis (Heath Ledger) on his inauthenticity, telling him he's no longer willing "to get by on a few high-altitude fucks a year".

In The King's Speech, this is where Logue tells Bertie that the nation needs him in its hour of need – not the distracted, Nazi-apologist David – and Bertie calls him treasonous. But that's just a rationalisation, because, as in all the great stories, the hero has just been "confronted".

Read more about the Ordeal or Midpoint

Step 9: Reborn (The Reward)

Having been confronted with their flaw at The Ordeal, the old, flawed Hero will have died, and a new, "reborn" Hero will emerge in this sequence.

After the "sweaty-tooth madman" scene, Todd's shy, retiring identity crumbles away and he is "reborn" as the hero who will literally take a stand at the moving climax of Dead Poets Society.

If they've been cowardly, they'll now display courage. If they've been selfish, they'll now demonstrate compassion. But, more importantly, their transformation will be revealed through the fresh perceptions of those around them.

In Dead Poets Society, after Todd has revealed the lyrical poet inside his diffident shell, Neil (Robert Sean Leonard) looks at him in awe and Keating says to Todd, "Don't you forget this". He doesn't.

In An Officer and a Gentleman, after Zack has finally shed his insouciant wise-guy identity in the "I've got nothin' else" scene, he makes Perryman feel like a heel because he's shined his belt buckles and boots. "Son of a bitch".

In Groundhog Day, this is where Phil finally stops trying to seduce Rita and instead talks lovingly about her – "you like boats, but not the ocean" – in a way that suggests he genuinely cares for her, rather than viewing her as just another conquest. Rita can see the change and responds to it.

Good cinematic storytelling is about squeezing and releasing your audience, and, after the drama of The Ordeal, this sequence definitely is about lifting the foot off the pedal a little.

In The King's Speech, this is where we have the delightful – if apocryphal – scene where Bertie and "Liz" visit Logue and his wife at home. It's comedic and warm and gives the audience a breather before the tension that lies up ahead.

If you've just put your hero through a confronting Ordeal, in this sequence try to lighten the mood and through the reactions of those around the Hero, reveal that this character has been "reborn".

Step 10. Desperate (Road Back)

In the last sequence, the Hero was feeling pretty good about themselves because they'd just climbed their personal Everest, but in this sequence they have a daunting realisation: now they've got to get down.

This is where some complication occurs that makes the attainment of the Hero's original goal seem much more difficult or downright impossible.

But it's not just about plot. It's not just about being in a dire situation. If you want to tell a great story, at this point it can help to present the hero with a dilemma – to put them between a rock and a hard place.

In Billy Wilder's The Apartment, C.C. Baxter (Jack Lemmon) is forced to choose between advancing his career and honouring his love for Miss Kubelik.

In an earlier post, I explore this crisis in great detail, but in summary it's about forcing the Hero to choose between what they want and what they need.

Very often, the choice is between a material goal and love.

In Tootsie, Michael reaches the point where he has to choose between what he wants – paid work as an actor – and what he needs – Julie. He can't have both.

In Moonstruck, Loretta's fiancée, Johnny, returns from Sicily here, which means that she's soon going to have to choose between marrying a man whom she merely likes, or taking a risk on love again with his more passionate brother, Ronny.

In Billy Wilder's sublime The Apartment, C.C. Baxter (Jack Lemmon) has to choose between continuing to allow his boss (Fred McMurray) to use his apartment for his trysts – or becoming a "mensch" and taking a stand in honour of his love for Miss Kubelik (Shirley Maclaine).

In Strictly Ballroom the choice that Scott is presented with here is not about love but about integrity. If he dances the Federation's steps, he'll win the prize he's always coveted but feel nothing. If he dances his own steps, he'll not win but he'll gain a greater prize – the fulfilment that comes with genuine self-expression and integrity.

Not every film offers up this sort of dilemma. But, if you don't force your character to make a choice, you have to ask yourself how your hero is going to prove to us that they have been transformed. If all they do is get what they always sought, without sacrifice, without compromise, you're heading towards a hollow conclusion. I would suggest The Fugitive, after a brilliant opening, falls into this trap.

So often is the hero faced with a choice at this point that for a time I referred to this step as "conflicted". But, to make the paradigm more universal, because the combination of the dilemma and other obstacles generally make this the Hero's darkest hour, I now think that the place you want to take your character is "desperate".

Read more about how to create a dilemma at the Crisis or Act 2 Turning Point

Step 11: Decisive (Resurrection)

This is it showtime. This is where the dramatic question that was raised in Act 1 is finally answered. More importantly, it's where we discover whether the Hero will take this opportunity to prove to us that they have indeed been transformed by their journey.

In When Harry Met Sally, the pessimistic protagonist decides that maybe fancying a woman and being friends with her aren't mutually exclusive after all.

It's not about winning and it's not about saving the Hero's arse. They can't be rescued by external forces because that would deny them their ultimate character test. (Date Night makes this mistake.)

That's why I call this climactic sequence "decisive". It demands that the hero be the active agent – that they make the choice that determines whether they are going to draw on the better part of their humanity or fall back into the weaknesses of the past.

In Schindler's List, Oscar, having amassed the wealth he sought at the beginning, now chooses to use it to save the lives of his Jewish workers.

In North by Northwest, mummy's boy, Roger Thornhill, chooses to ignore his chance to escape and instead go to try and save Eve Kendall up on Mt Rushmore.

In When Harry Met Sally, Harry chooses to shed his pessimism about male-female relationships and run to Sally on New Year's Eve because "when you've decided you want to spend the rest of your life with someone, you want the rest of your life to start as soon as possible".

But just because the Hero is decisive, it doesn't mean the ending has to be "happy". It just has to be satisfying, which it can be if the Hero loses the external battle but wins the more important personal war with their demons.

At the end of Thelma and Louise, the protagonists perish but the audience goes with it because spiritually the two leads have evolved.

In Brokeback Mountain, Ennis chooses to go to Jack's parents to collect his ashes (and his shirt) in an act that admits for the first time that the love of his life was a fellow cowboy.

In Dead Man Walking, Matthew Poncelet (Sean Penn) chooses to confess to his crime so despite the fact that he's executed, we feel an incredible sense of catharsis.

In Thelma and Louise, they choose to drive off that cliff because, though their flesh may perish, their souls are free to soar (and this is coming from a devout atheist).

Give your protagonist a choice at the Act 2 Turning Point, and if they're "decisive" at the climax and prove to use that they've been changed by the journey, there's every chance you'll pull off a moving finale.

Step 12: Complete (Return with the Elixir)

Ennis is aching at the end of Brokeback Mountain but it's a soaring finale because his character is wiser (and it's got a cracking soundtrack).

When you watch the 100m Final at the Olympics, you don't go home after the race is run. You stay for the medal ceremony. That's what this sequence is all about. We've just witnessed some heroics at the climax; now we want to stick around to soak up those overwhelming emotions.

When we first met the hero back in their Ordinary World, they were "incomplete". Rick Blaine in Casablanca was hiding from the world. Loretta was about to marry a fool. Oscar Schindler was more concerned about the wine list than the plight of the Jews.

But the story has forced them to confront their flaws and, at the Climax, prove that they've addressed them. Their material circumstances don't really matter. And it doesn't matter if they're not free from imperfection. Just so long as we sense that, spiritually, they're complete. That's what happens here.

In Groundhog Day, Mr Keating gives Todd and the boys standing on their desks a nod that says, "My, how you've grown".

In Brokeback Mountain, even though Ennis has only a flannel shirt to remind him of Jack, we know the character has gained the wisdom that we can't choose in what form love comes to us.

In Little Miss Sunshine, they all fail to get what they want, but they get what they need: the family is "complete".

In Little Miss Sunshine, 7-year-old Olive has scandalised the contest, Richard hasn't got his book deal, colour-blind Dwayne can't fly jets, Frank is possibly only the second most important Proust scholar in the United States, and the smack-addict Grandpa has OD'd and is curled up in the trunk of the Kombi – but at least now the family is whole.

And, in The King's Speech, when Bertie thanks Logue, "My friend", and his therapist for the first time calls him, "Your majesty" you again get this sense that our Hero, after all their travails, is finally "complete".

Summary of the Hero's Emotional Journey

That's the Cracking Yarns take on the Hero's Emotional Journey. I'm not suggesting you jettison Chris Vogler's Hero's Journey. That's still the bible as far as I'm concerned. But hopefully this will give you a more character-oriented way of thinking about story, and maybe it will encourage more people to explore what Campbell identified and Vogler brought to the attention of film-makers all over the world.

Hero's Emotional Journey Hero's Inner Journey Character Arc Vogler