DB here:

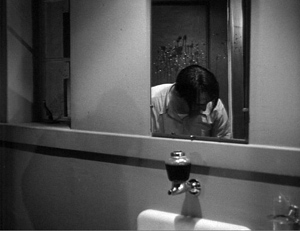

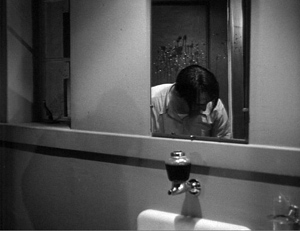

The mobster Joseph Rico is in protective custody; tomorrow he testifies against the big boss. But Rico fears reprisals, so he decides to escape. While a sleepy cop guards him in the washroom, he bends over the sink and rinses his face.

Turning so suddenly that water spatters on the mirror, he grabs the cop in an armlock and slams his head against the sink, just below the frameline.

Rico turns to the window to make his escape.

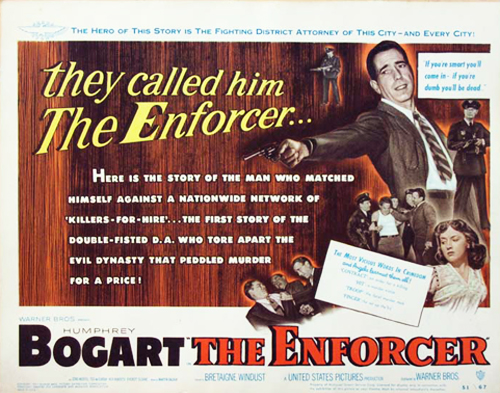

What interests me in this passage from The Enforcer (1951) is not just what happens in the mirror but also what happens on it. While Rico belabors the cop's head, we're given a chance to notice the splash of water that hit the mirror when Rico whirled to the attack. While the action is moving forward, we're reminded of what had triggered it.

We get a sort of parallel reminder in the next scene, when we see the wounded cop again. He's sporting a big bruise on his left temple, a souvenir of Rico's assault.

Pfui. Details, you might say. Or you might (correctly) instance this as another case of Charles Barr's enlightening notion of gradation of emphasis. But it's worth getting a little more specific, because even this simple scene (by non-auteur director Bretaigne Windust) offers us something to think about, and something for today's filmmakers to try.

Most films today don't fully exploit the visual dimension of cinema. True, we have dazzling CGI and fancy camera moves. But when it comes to less flamboyant scenes, directors have limited their options by relying too much on stand-and-deliver and walk-and-talk. There are other aspects of visual storytelling that today's filmmakers neglect. One aspect is the possibility of gracefully moving actors around the set in a sustained fixed shot. A specific tactic I've mentioned before is the Cross, and another involves ways to get people into a room. The option I'm going to sermonize about today is what I'll call scenic density.

By scenic density I mean an approach to staging, shooting, and cutting in which selected details or areas change their status in the course of the action. I don't count the bustle of background business, all that street traffic that is so much pictorial excelsior in our movies. Nor do I refer to stuffing the setting with desk and kitchen flotsam, allusive pop-culture posters, and the other distinctive "assets" that will be exploited when the film's world gets transposed to a videogame. I mean something more expressive and intriguing.

Using it up

Go back to the Enforcer scene. The shot's composition creates a delimited zone of action. The guard cop is framed tightly in the mirror. When the fight breaks out, it's initially framed in that mirror–a narrowing of visual importance. Moreover, the shot is designed to highlight the spatter on the mirror. It's fairly prominent, stuck near the center and, providentially, in the spot that the cop's head initially occupied. The lighting picks out the drips, and in a shot where the figures move in and out of frame, there isn't an equally constant center of interest. We're probably concentrating on Rico's punishing of the cop, but the dribbles of water remain prominent enough to claim our interest, especially when Rico passes out of frame.

So here's my first condition for scenic density: the shot keeps several items of dramatic significance salient in the composition.

This technical choice asks the filmmaker to think of the frame as a field of dynamic masses and forces. Such an idea was part of the aesthetic of "advanced" European and Japanese silent cinema of the 1920s. Many directors explored this dynamism, often aided by low angles and wide-angle lenses. Here are examples from Eisenstein's Old and New and Murnau's Tartuffe.

This pictorial density became especially prominent in American cinema during the 1940s, when low angles, wide-angle lenses, and locations and smaller sets encouraged cinematographers to pack their compositions snugly, as in this shot from Panic in the Streets.

Boris Kaufman, cinematographer for Jean Vigo and Elia Kazan, summed up the principle:

The space within the frame should be entirely used in the composition.

Since cinema is a time-bound art, however, the salient elements in the shot could and should change. But if the frame space is wholly "used," what room is there for change? The only options are to have the using-up elements shift position, or to reveal that the frame isn't used up.

Vivid instances, also from the 1940s, can be seen in Anthony Mann's work, both with and without John Alton. Generally, Mann used the new fashion for depth composition, especially big foreground elements, to heighten scenes of violence. Physical action becomes more aggressive if people rush the camera and halt in tight close-up, especially because wide-angle lenses tend to accelerate movement to the foreground. Mann thrusts violence abruptly to the camera with an almost comic-book effect, as when the club owner is shot in Railroaded, or a man is flung to the floor in Raw Deal.

Even when this in-your-face tactic isn't employed, the Mann films find ingenious ways to develop what seem to be completely locked depth compositions. In Border Incident, Ulrich confronts the Mexican government agent Pablo, disguised as a Bracero. A looming depth shot is followed by a reverse shot displaying a compact composition.

Is the frame space fully used? The second shot above is opened up when Ulrich leans forward to sock Pablo, creating a vacant spot on the far right for Pablo to fall into. The shot is emptied and re-filled, dense once more.

Memories, memories

Aha, you may be saying. Density just refers to squinchy, fussy shots from an era that favored cheap flash. No. The Enforcer shot isn't all that cramped. Of course the blank, unchanging walls serve to highlight the mirror-reflected fight and the water dribbling down the glass, but you can imagine how much more jammed and skewed Mann's treatment of Rico's escape would be. As for the flashier depth, I just needed some clear-cut cases of density, examples in which details and spatial zones become starkly salient. Now I want to suggest that scenic density can be achieved in something more spacious, even monumental. That has to do with time and memory.

Part of what gives the Enforcer shot its interest is the superimposition of two moments of action in a single space: Rico's diversionary turn from the washstand, recorded in the splash he made on the mirror, and the struggle taking place a few seconds later. A further trace of that struggle and that splash is visible in the bruise on the cop's head in the next scene.

That dripping spatter can stand in for the second quality of spatial density I want to highlight: Its capacity to coax us to recall earlier action in the locale. Characters leave their marks and spoors in the space, and those get activated as memories. Unlike the slick surfaces of today's settings, in classic films the settings can bear the impress of human transit, leading us to recall bits of behavior and emotional states. Let me illustrate from Lang's Hangmen Also Die (1943).

It's Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia, and Gestapo Inspector Ritter is questioning Mrs. Dvorak, the vegetable seller who could identify the woman who misled the officers pursuing an assassin. Torture, or at least what we think of as torture, hasn't started. She is simply standing in front of his desk as he brandishes his riding crop in the manner of a good movie Nazi.

When Mrs. Dvorak denies knowing the woman, Ritter taps the back-rest of the chair. It simply falls off, and we realize it's not fastened to the chair.

Ritter says, "Pick it up again." Now we realize that intimidation has been applied for some while; Ritter has made the woman stoop to replace the back-rest many times. She does so again as the camera tracks back. This is nicely detailed too. She starts to pick it up by bending over, finds the effort too painful, and then goes to her knees to pick it up–just as Ritter taps his riding crop against her hand, a teacher gently chiding a slow pupil.

As Mrs. Dvorak rises to put the piece back in place, the camera pans slightly right to pick up the woman bringing in a tray. Happily Ritter sniffs the coffee jug and resumes questioning the old woman.

Cut to a shot of her by the chair. "Let's start from the beginning," says Ritter, offscreen. Unthinkingly Mrs Dvorak starts to rest her hand on the loose slat, forgetting that the top slat is unattached. It's a natural response. She's been standing there for a long time and would like something to rest on, and the chair is temptingly close. (Presumably, that's its purpose, to taunt the unwary prisoner forced to stand a long time.) Remembering just in time, she yanks her hand away. If she knocks the back-rest off, she'll just have to pick it up again.

Cut to Ritter. "Don't be nervous, Mrs. Dvorak. I'm prepared to—"

Cut to Mrs. Dvorak. As he continues, "–devote to you all of tonight," she forgets herself again and relaxes her hand, this time on the back-rest. It falls off, making her start.

She looks up as Ritter says, offscreen: "Even longer if necessary." Cut to Ritter, gesturing with a piece of sausage and saying, coaxingly, "Well?"

Slowly she goes to her knees again as the camera tracks in on her.

Back to Ritter: "That's the girl." Back to her, rising in pain to replace the back-rest.

The scene concludes with Ritter reminding Mrs. Dvorak that she's in Gestapo headquarters. She acknowledges that she doesn't expect to leave without giving information. He starts his questioning all over again as the scene fades out.

This quietly suspenseful scene establishes a bit of furniture as a key prop. Once the faulty back-rest is marked for our notice, we're expected to remember that it's a means of intimidation–something that Mrs. Dvorak, in her anxiety about refusing to aid the Nazis, twice forgets. Lang's shots, simple and uncrowded, makes the chair, like the spattered mirror in The Enforcer, preserve the trace of human activity. Yet it's more acutely integrated into the scene's drama than the mirror, and remembering how it was used earlier makes us wait tensely to see how it will be used again.

Long-term density

Several scenes later, the Nazis threaten to kill four hundred Czech hostages if the assassin isn't turned over to them. Mascha Novotny has set out for Gestapo headquarters to denounce the man she helped, but she changes her mind and decides not to betray her country. She will only plead for her father's life. Once more we're in Ritter's office.

Centered in the frame, standing out as a pale oblong against the grayer background, the fateful chair is made salient during Mascha's conversation with Gruber. I suspect there's a sort of spatial suspense here–will she move to the chair and dislodge the precarious piece of wood?–but more important, I think, is the fact that the chair ineluctably reminds us of Mrs. Dvorak and her quiet resistance to pressure.

Ritter leaves to consult his superiors. When he comes back, a new composition keeps the chair prominent and lends a new centrality to the clock on Ritter's desk, surmounted by a snarling cat or something like it. (It's visible in shadow in the earlier scene with Mrs. Dvorak.) But now the camera arcs to minimize the Dvorak chair and show the beast and Ritter targeting Mascha.

Soon enough, as if to make sure we remember, Mrs. Dvorak is brought back in, having undergone serious torture. The camera positions reactivate our memories of the earlier scene.

As she continues to lie to protect Mascha, Mrs. Dvorak never touches the chair. Although she has been tortured, she seems wearily defiant, as if her refusal to aid the Nazis has given her some strength: no need to lean on the chair now. As a final cue to our memories, Lang has Ritter play once more with his riding crop, letting its shadow fall on her heart.

The threat is clear: For lying, the old woman will pay with her life.

The chair reappears in a later scene, but I'd argue that then it serves more as a pointer to another prop. The resistance movement fights back by framing Czaka, a beer baron sympathetic to the Nazis, as the assassin. Lang could have explicitly recalled the questioning of Mrs. Dvorak by having Czaka lean on the slat and knock it off. Instead, the composition makes Ritter's clock more important than it was in earlier shots. As Czaka tries to defend himself, the framing blocks our view of the chair but emphasizes the snarling catlike creature on top of the clock. And the chair has shifted a little off and become a bit darker; it's no longer as salient.

This cluster of scenes from Hangmen Also Die illustrates how scenic density can add layers to a film. One scene recalls another not only by similarity of situation and locale but by tangible marks left on it by earlier action. Having seen Mrs. Dvorak subjected to Ritter's oily intimidation, we generally expect something like it to be applied to Anna. This conventional situation is given a rich, concrete presentation by the repeated camera positions and the simple chair that, unmoving, enters into the drama.

Of course as a Hollywood director, Lang was pressured to reuse sets and camera setups. That saved money and time. But he turned such repetitions to his advantage by letting certain objects come forward at crucial moments. They not only become part of the drama but prime us to remember them, and what they revealed, in ensuing scenes. And even though Lang never pursued the aggressive, packed deep-focus of other directors working in the 1940s, he shows how roomier, less pressurized compositions could still be charged with echoes of earlier bits of behavior.

Is this sort of visual-dramatic economy, calling on precise memories of concrete actions, lost in today's American cinema? I suspect it is.

In studying Hangmen Also Die, I was curious about a perennial problem. Was the byplay with the chair a Lang invention on the set, or was it some version of the script, or in the original story by Lang and Bertolt Brecht?

The film didn't have a secret script, as the poster says, but the sources do remain a bit obscure. A draft of the original story signed by Lang and Brecht, in that order, exists. It indicates only that the greengrocer, called Frau Blaschke, is subjected to eight hours of "the usual Gestapo brutality" and refuses to identify the girl. There were other drafts of the screenplay, but I don't have access to them, if they exist, and standard sources on Brecht in Hollywood don't mention this scene's details.

Somewhere along the line, though, the chair-back business was concocted. I found the shooting script signed only by John Wexley (Brecht claimed that he was robbed of credit) and annotated in pencil, perhaps by Lang. That script indicates that Ritter's room contains "a vacant chair with its seat close against desk." and Mrs. Dvorak is standing beside it as the scene begins. Much of the dialogue is the same , with some slight changes notated in pencil, possibly by Lang. But the camera movements indicated are different from those in the final film, and more importantly so are the actions. After Mrs. Dvorak claims that she doesn't know the woman who helped the assassin, we read the following. I indicate pencil notations with {}.

In her fatigue, she places hand on back-rest of chair. But its dowels are loose and back-rest clatters to the floor.

RITTER (saccharine): Pick it up, Mrs. Dvorak.

CAMERA MOVES IN CLOSE as she obeys, stooping with painful fatigue–she has done this many times tonight.

RITTER: Now put it back in place, Mrs. Dvorak.

(She does so)

As Ritter questions her:

MED. SHOT – MRS. DVORAK. Without thinking, she is about to place hand again on loose back-rest–when she remembers and jerks back.

RITTER'S VOICE: Now don't be nervous, Mrs. Dvorak…I'm prepared to devote to you all of tonight–and even longer, if necessary.

Mrs. Dvorak, unconsciously reacting to this, once more rests hand on chair. {She jerks back but} The piece of wood clatters to the floor.

MED. SHOT – RITTER. Ritter waits patiently; when she doesn't move, inquires:

RITTER: Well…?

CAMERA PULLS BACK to INCLUDE Mrs. Dvorak, who stoops to repeat painful routine. Ritter smiles approvingly.

RITTER: That's the girl.

Nothing here is indicated about Ritter's riding crop, nor does he initially knock the back-rest off the chair. Mrs. Dvorak does it herself, accidentally. And the scripted line is "Pick it up, Mrs. Dvorak," not, as in the finished film, "Pick it up again, Mrs. Dvorak." The film version makes it clear that the byplay with the backrest is part of Ritter's softening-up technique, something indicated in the script but not spelled out.

The later scenes in the film show other differences, mostly additions of things not mentioned in the shooting script. For instance, the script doesn't mention the shadow of Ritter's riding-crop. But the excerpt shows that the shooting script points toward some of the detailing we find in the finished film. It provides the sort of nudges that a director, especially one as oriented to gesture as Lang was, could elaborate on the set.

The Lang/ Brecht story has been published as "437!! Ein Seiselfilm," in The Brecht Yearbook vol. 28: Friends, Colleagues, Collaborators, ed. Stephen Brockmann (2003), 9-30. The passage I mention, kindly translated for me by Ben Brewster, is on p. 16. Broader background on Brecht's adventures in Hollywood can be found in James K. Lyon, Bertolt Brecht in America (Princeton University Press, 1980). Chapter 14 of Patrick McGilligan's Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast (St. Martin's, 1997) offers an account, mostly relying on Brecht's viewpoint, of the making of Hangmen Also Die. The shooting script is in the John Wexley collection of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research and the State Historical Society here in Madison. Thanks also to Marc Silberman, renowned Brecht expert, for advice.

You are my density | David Bordwell