Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Note: Michael Shannon + Chinese Film

Interview - Director: Bennett Miller (Moneyball) by Anne Thompson

How Did Moneyball Director Bennett Miller Make a Smart Studio Movie? Brad Pitt.

Bennett Miller is not the first name that would come to mind as the director ofMoneyball, which two years ago was a problem-plagued project stalled at Sony with $10 million in costs stacked against it from past writers Stan Chervin, Steve Zaillian and Aaron Sorkin and departed directors David Frankel and Steven Soderbergh. And yet, for many reasons, Miller was just the right fit for this Sony adaptation of the 2003 Michael Lewis bestseller about Oakland As general manager Billy Beane. The movie launched toraves at Toronto and beyond and opened well this weekend. Now Oscars are in its sights.

Miller had something to prove, after not having directed a feature since 2005's Capote, made with his two Mamaroneck buds Dan Futterman and Philip Seymour Hoffman, who won the Oscar. (Miller's been directing commercials.) Moneyball is the New York director's third film, and his first studio assignment. The reason Miller got the job, finally, was that he and Brad Pitt hit it off when they met on a film that never got off the ground at MRC, Foxcatcher, the story of DuPont heir John E. du Pont, who was convicted of killing Olympic wrestler David Schultz.

Thus, after Sony's Amy Pascal pulled the plug on Soderbergh's experimental vision ofMoneyball, Pitt brought Miller in to direct the baseball film, and stuck by him through thick and thin. Miller pitched his idea of the movie, focusing on Beane as a disappointed, stubborn, competitive guy with something to prove—a subject the director knew something about—and Pascal went along. Amazingly enough, when Miller's idiosyncratic, naturalistic, slow-paced, non-glossy director's cut got to research previews, it played. For once, his movie was saved by movie fans.

Anne Thompson: Moneyball is unexpected from a studio movie. Which script did you first read?

Bennett Miller: I first read the script that was Sorkin's first revision of Zaillian, and then I read Zaillian and then I read the book. Then I thought about if there was a movie somewhere. Then I met with Brad, and pitched him. Everybody's gotta be making the same movie, otherwise you're in a disaster, especially with these huge personalities. With them, Might can be your best friend or your worst enemy. If you're sharing a common goal, purpose and vision, then great, and if not, it's the last place anybody wants to be.

AT: So you really deliberated about taking the job?

BM: Because: What's the movie? Is there a movie? Can it get made? Is it realistic, given more money than Capote or the other movie I was trying to get made that didn't get made? Can this get made with a larger budget at a studio, when you're coming onto something that already has a past?

AT: A checkered past. There are reasons why it was difficult. You probably understood the authenticity Steven Soderbergh wanted to bring, on some level?

BM: The immediate answer is yes. But also I think he left it too open to a process that was going to discover and reveal, that we can't know exactly what would have been.

AT: That's why the studio pulled out. Whereas you were in effect proposing a more predictable outcome? But it's always risky.

BM: Yeah. (Pause) The truth is that every movie teaches you how to make that movie, and this one really had its own demands, independent of what anybody would have liked it to have been. It wanted things and needed things, and it really kept revealing itself right until the end. So I don't think it's right to say that it was predictable. From an executive's perspective, you could say that, sure.

AT: So did the studio eventually just sign off and say go for it?

BM: Well, how long have you been in this business? I mean, come on. I don't think there's anything sensational about how it gets worked out, but it's like anything, making a movie at a studio, passing legislation, whatever—it's complicated.

AT: Did it turn out better or worse than you expected: working with the studio and making the movie?

BM: Honestly, I feel like I went in there with open eyes. I had never taken an interview with a movie at a studio before, after Capote. And so I thought, 'oh, maybe I could do a Trojan Horse-type experience.'

AT: With Moneyball. What happened to The Immortalist with Vanguard/Paramount/John Lesher? You were working on that for a few years.

BM: And something else, too, called Foxcatcher at MRC, which is the one I'd committed to doing next. And the world didn't cooperate. Things were falling apart. Both things I want to do still. I have the rights, but until you see the end credits roll on opening night…

AT: You've learned the hard way. But now, you're in The Show.

BM: I'm in The Show. I've learned a lot.

AT: How did your name get thrown into the mix?

BM: I believe it was Brad. I had met him before and talked to him about Foxcatcherand when I flew out there to have a conversation we definitely bonded, we were feeling the same thing. Moneyball would not have been possible if he and I were making a different movie.

AT: How exactly did you describe your take on the movie to the likes of Pitt, Pascal, and producers Rachael Horovitz, Mike DeLuca and Scott Rudin?

BM: I liked a couple of lines from the book that reflected on Billy's past and what might be going on beyond what Billy was aware of. Michael Lewis had said that Billy wondered if there was a different life he was supposed to be leading.

AT: He didn't go to Stanford, he wasn't good in the batter's box.

BM: He wanted to be a student. He was really smart. Nobody in his family had ever gone to college, and he wanted to be the first. His mother really did not want him to go [to The Mets]. She wouldn't be in the room when he signed the contract. He was a first round draft pick! From the time he was fifteen, you've got adults who've spent their lives in baseball, they've seen everything, saying ,'This is your future, this is your destiny,' and he makes a decision based on that, and there's a big check. Again, there'd be a big check at the end of the movie, and I thought, 'well that's one thing; there's a check and a check, and a decision and a decision.'

The other thing: Michael describes Billy's excitement when these new [sabermetric] concepts are introduced to him, as not just a way of winning, potentially, but as ideas that might explain him and his outcome, and why he might have failed. To me, he thinks he's trying to win baseball games, but he's really trying to remedy something in his own life.

AT: He couldn't stand being a failure: why did all the baseball experts think he was meant to be something that despite all his gifts, he didn't turn out to be? It didn't work out. He didn't trust those people.

BM: Well he wanted to prove them wrong, and that season became a kind of trial. And the outcome would be some kind of verdict that would have something to say about who he was. He's trying to remedy something from his past and he wanted to put the game on its head, and there's a little hostility in it.

AT: He was competitive.

BM: Extremely competitive. When I read it, I saw it as a really small story, in a way it used to be OK to make a small story, like a Cuckoo's Nest, where it's like, nobody knows about these people. But this is bigger in scale.

AT: That's what I like about it. It has no gloss to it; I don't mean that in a negative way.

BM: That's the intention.

AT: How do you make a studio-level movie with a movie star and all these players and still bring your aesthetic to it? Because it's still a Bennett Miller movie.

BM: How? You have Brad Pitt as an ally. That's it. It really was his passion that got the movie made. It's a great part and he wanted to do it.

AT: It was also a commercial movie, even if it's not glossy.

BM: In my mind, I think that equals a more commercial movie, because I think nobody wants to see a baseball movie, or a light comedy baseball movie. Nobody cares, nobody wants that. That's the surface of the thing and that's actually the obstacle to selling the movie, but if it's something that people can relate to, i.e. nobody's life turns out the way they expect it's gonna be, it just doesn't happen. And nobody does not question at one point or another, 'what else might my life have been?' and the decisions you make. And also be reminded how hard and in a small way how heroic it is to challenge perceptions; your own and other people's.

AT: People respond to the idea of a rebel going up against the establishment.

BM: Absolutely. My point is that those things are commercial when they're given an opportunity. And in baseball, in a similar way, they want to keep betting on the same five tools, we're making this at a studio and there might be that impulse to revert to the gloss or the swelling score or the jokes, and I never believed that that would be more commercial than something that has less gloss, that you could relate to. I think that is the big market that is overlooked.

AT: The screenplay, how much was Zaillian, how much Sorkin?

BM: Both of these guys came on and off it. It went Sorkin, Zaillian, Sorkin, Zaillian—it was a little bit of back and forth.

AT: Well you're working with two of the best screenwriters we know. What were the strengths of each one?

BM:A guy could do worse! Zaillian had a heavier, earthier, more internal, brooding, darker perspective. And Sorkin is masterful at comedic haiku that communicates volumes in a moment, in a beat, that he could take a scene that's written and he could reduce it and put a line in and make it function in a different way. But ultimately what we're talking about is a character, the public and private self, like Capote. These guys wrote appropriately to different sides of him. Zaillian wrote more to the internal, beneath the surface, and Sorkin managed to write very effectively for the more public, charismatic side of Billy.

AT: Cinematographer Wally Pfister (The Dark Knight, Inception) was a good choice. He's unpretentious, very gifted, doesn't go for gloss. He keeps it on character, on what's really going on.

BM: Wally comes from news and documentary; has a very on-his-feet, verite style, he's the best operator I've ever worked with. He rolls into an environment and doesn't want to create something out of his imagination—all of which make him a really comfortable fit for this stuff. He'll walk into an environment and say, 'Well, what is it, what are the sources, and how do we wrangle that in and make it manageable and allow us enough time to shoot the damn thing?'

AT: How did you cast the baseball scouts?

BM: We met a bunch of scouts, interviewed them, did research. I think there are three actors.

AT: The one that gets fired?

BM: He has done some acting but he's a baseball guy for thirty-something years. He introduced me to those guys, they all know each other. I did a baseball-themed commercial about two years ago and Kenny came in to audition and gives me his dossier and says, 'I was here, here, Yankees,' and I said 'What do you think of Billy Beane?' and he says, 'Ruining the game.' I said 'Why?' and if had I been able to get a quarter of what he did in that monologue…

AT: And Jonah Hill: where did those long slow reaction shots come from?

BM: It just became a character thing. In baseball everyone's kind of operating from the gut and shooting from the hip. He's a very thoughtful guy. There's not a lot more interesting than watching somebody think on film. And the movie really ends with a decision, like you don't hear him, it's not expressed in any way, you're just sitting with a guy as he's having an emotional experience and the decision is being made. Jonah brought that, and when we were cutting it, I liked it so much, we found ways to manufacture it here and there. It's a character thing, of a thoughtful, deliberative person. Like he hesitates, thinks, measures twice, speaks…and it's funny.

AT: How was it to work with Pitt?

BM: He's got two things. One is a shamanistic ability you can't really describe. He understands how to be fascinating, and conjure a presence. He could have been a ballet dancer, he exercises a kind of control over his instrument, he understands the frame like a painter, he knows how to enter it. It's the only experience I've ever had where watching the dailies is different from what it's like being in the room, it made watching the monitor more important. He's doing a leading role, but I see him as a character actor. In this case, you have to tell the story, with your performance, you're leading the audience through your story. It's a personal story to him, he wanted to play the role. You need to be making the same movie and telling the same story. Is it communicating? To the degree that you can relate to the movie it will work and when it feels like you're being put on, it won't work. It didn't want razzmatazz and slickness.

AT: What was the most challenging thing to pull off on this film as a director?

BM: The material itself was challenging. It did not lend itself naturally to a cinema experience: Michael's book, the story, which is so much about numbers and stats, you can't ignore that, it was difficult. Hopefully at the end of the day, it was a clarified vision, but getting there is like a football size suduku puzzle. The movie is a little like that.

AT: How was the editing process?

BM: The movie was revealing itself until the last moment. The spirit of the thing is very clear, and the way it was gonna happen was never by a complete prescription. And so I don't remember how many months we edited for, but maybe nine, it was lengthy and laborious. It was a very creative period, meaning you have to keep on finding ways to make things work.

AT: How would you characterize what you were fighting to keep in the movie?

BM: If you have a vision for something, things are navigable. If it gets fuzzy, then obstacles become much more formidable. At the end of the day, someone has to show up and do the thing and there's a choice to either stick to what you believe and see, or to attempt to helm something that you don't really understand or appreciate that somebody else would argue for.

AT: Your movie has ebbs and flows and character beats that studios don't jump up and down about when they are looking for mainstream acceptance. It's not the way they would have done it.

BM: It's the same exact thing as the story itself; you need guys who are fast, you need as many tools as possible, these are the ingredients that make up a successful team or a good player or a hit movie—and you say, well, those aren't necessarily the ingredients, you don't necessarily need to have a movie of this length, or moves along at this pace, or has a joke or a cut every so often. In the case of this movie it happens that the focus groups were validating. From the first one, it was a revelation that you can trust the things that made this book a bestseller, you can trust the themes that are non-debatably universal and meaningful to people. Just trust THAT. Make it feel relatable. That will suit your purposes, too.

People are attracted to entertainment, for sure, or jokes, excitement and romantically heightened stories that might be false, but are still attractive fantasies. But they're also interested in this other thing. It's not like, I'm against this or any of those things. There's something to aim for; there's a vision there, it's about serving these things. it's allowing it to be a small, personal story that has an outcome that defies the traditional tropes and climaxes and conclusions of a sports movie with champagne corks. It's a quieter, more personal, longer lasting, I think deeper, more meaningful triumph.

How Did Moneyball Director Bennett Miller Make a Smart Studio Movie? Brad Pitt.

Monday, September 19, 2011

Scriptography | David Bordwell

Hollywood screenwriters at work, according to Boy Meets Girl (1938).

It's not every conference that opens a morning session by asking the men in the audience to take off their underwear.

But I anticipate.

Last weekend I was a guest of the Screenwriting Resource Network's fourth annual Screenwriting Research Conference in Brussels. I think that a hell of a time was had by all, and I learned quite a bit, including some reasons why people are interested in screenplays.

Schmucks with Underwoods

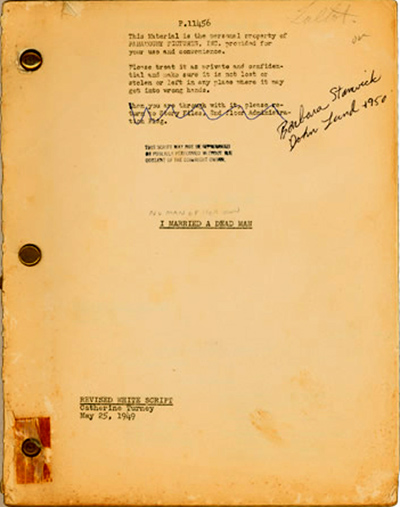

Catherine Turney script for No Man of Her Own (1950).

In my youth, there seemed to be a solemn pact among my peers that we would never study certain areas: censorship, audiences, adaptation (novels into film, particularly), and screenwriting. An earlier generation had, through patient labor, shown decisively that these subjects were dead boring. We, on the other hand, were fired by notions of the director as auteur, and indifferent to what were called "literary" and "sociological" approaches to film. So we triumphantly turned toward The Text—that is, the finished movie.

Things have changed since then. Yet there are still tempting reasons to consider the study of screenwriting a nonstarter if you're interested in cinema as an art. If you think of the finished film as the achieved artwork, then study of screenplay drafts risks seeming irrelevant. Whatever the screenwriter(s) intended seems irrelevant to the result. So what if six or more screenwriters labored over Tootsie? The movie stands or falls by what we see onscreen.

This was the view presented in Jean-Claude Carrière's three talks to our group. He suggested that the screenplay is destined to become landfill, and rightly so. It's like the caterpillar that becomes a butterfly. Once the film has been made, the script has no intrinsic value.

Someone might say, "Wait! We study a painter's sketches, a novelist's drafts, or a composer's early scores. These materials can contribute to understanding the finished work, and sometimes they have an artistic value of their own." The problem is that in these arts, the preparatory materials are in the same medium as the result. But a script can't count as a version of the film because prose can't adequately specify the audiovisual texture of a movie. It's commonly thought, plausibly, that giving the same script to two directors would result in significantly different films. So the script is at best a series of suggestions for filming, not a sketchy version of the movie. Why not discard it when the film is done?

The study of screenwriting has probably also lain in the shadows because of the proliferation of screenwriting gurus and how-to manuals. Every American over the age of eighteen seems to be writing a screenplay; the Cable Guy who visited me last week was working on two. So all the seminars and advice books have arguably put thinking about screenplays rather close to the amateur-script racket.

Moreover, screenplay studies seem to be part of a broader, paradoxical development in academic film studies. Today scholars have more access to films than ever before, thanks to video, festivals, archives, and the internet. Yet many researchers prefer to talk about everything but the film. More and more scholars want to study just those subjects that my cohort considered dull or irrelevant: censorship and regulation, audiences (composition, demographics, critical reception, fandom), and preproduction factors (storyboards, scripts). In addition, many academics have turned to bigger thematic ideas like film and architecture, film and the city, film and modernity. These trends of research usually make only glancing reference to actual movies, mostly mining them for quick illustrative examples.

In sum, many academics have abandoned the study of film as an artistic medium that finds its embodiment in important works. To get to know particular films more intimately, you increasingly have to go to the Net, to writers like Jim Emerson, Adrian Martin, and other sensitive analytical critics. Talking about screenwriting can seem to be another way of avoiding coming to grips with the intrinsic power of movies.

You can probably tell that one side of me shares some of the biases I've listed. But when I remind myself that what people should study aren't topics but questions, I cheer up quite a bit. For there are, I think, worthwhile questions to be asked about all these areas, screenwriting included. The Brussels event gave some good instances of resourceful, occasionally exciting research into them.

Based on my short acquaintance, most of the research questions seem trained on one of two broad areas: Screenwriting and The Screenplay.

In the trenches

Kinky & Cosy

Screenwriting can be thought of as a practice, a creative activity with both personal and social aspects. How, we might ask, do screenwriters or directors express themselves in the script? How does a media industry recruit, sustain, and reward screenwriters? What are the conventions and constraints at work in a particular screenwriting community?

Questions like this are somewhat familiar to me. When I wrote my first book, on Carl Dreyer, I had to examine his scripts (notably the unproduced Jesus of Nazareth), and that helped me understand his characteristic methods of researching and planning his films. Later, when I collaborated with Kristin and Janet Staiger on The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I recognized a more institutional side of things. We can see from the films of the 1910s that filmmakers were cutting up the space in fresh ways. But this wasn't a matter of directors simply winging it on the set. Kristin used published manuals and Janet used original screenplays to show that shot breakdowns were planned to a considerable degree before shooting. This habit made production more efficient and controllable.

Steven Price offered further evidence of this sort, which displayed some of his research on early scenarios for Mack Sennett movies like Crooked to the End (1915). Interestingly, Steven found that sometimes the later version of a continuity script was more laconic than the initial one. Perhaps the gags, once spelled out in the first draft, could be left up to the actors. This is the sort of thing he identified as a "trace" of production practices.

A parallel of sorts emerged in Maria Belodubrovskaya's paper on screenwriting under Stalin. The Soviets, admiring Hollywood efficiency, tried to come up with a similar system. But their efforts to produce films in bulk were blocked by a censorship apparatus bent on ideological correctness. No surprise there, I guess. But Masha showed convincingly that the very efforts to mimic Hollywood's "assembly-line" system also discouraged authors from submitting scripts. The writers thought (like many of their LA counterparts) that such a setup denied them creative freedom. In addition, the prospect of story departments providing a stream of screenplays ran afoul of the tradition that gave the director control of the final draft. And the role of producer, as one who could steer the whole process, didn't exist! So much for the Soviet Hollywood.

What about other media? Sara Zanatta traced out the process of creating Italian TV series. She reviewed some major formats (miniseries, original series, adaptations of foreign series) and then took us through the process of creating individual episodes. Interestingly, it seems that the Italian system, unlike US television, makes the director the boss of it all. Frédéric Zeimat explained how he gained entry to the local screenwriting community through his university education, including work in Luc Dardennes' workshop at the Free University of Brussels. Eventually he came up with a script that won prizes. He is about to become a showrunner for a sitcom.

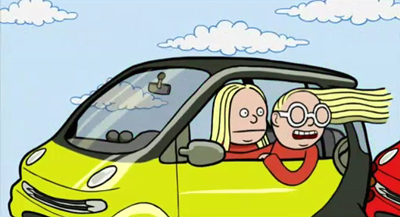

One of the most stimulating panels I heard considered the writing of graphic novels and animation. Richard Neupert explored how recent French animation sustained the tradition of individual authorship while still acceding to some international norms of moviemaking. The cartoonist Nix discussed how he faced new problems in transferring his three-panel comic strip Kinky & Cosy from print to television. TV demanded less written text, especially signs, so that the clips could be exported outside Belgium. More deeply, Nix had to rethink how to pace the action and leave a beat (say, two seconds) after the punchline.

Pascal Lefèvre, one of Europe's leading experts on comic art, provided a brisk, packed account of the history and practices of scriptwriting for Eurocomics. He described patterns of collaboration, format, and creative choice, placing special emphasis on comics as a spatial art different from cinema. His example was a page from Regis Franc's ulta-widescreen album Le Café de la plage. Here's a portion in which two periods of Monroe Stress's life coexist in a single space. He muses as an adult while his childish self gobbles up food under the guidance of Mom.

Comics space can also change abruptly, as when a window appears in second panel.

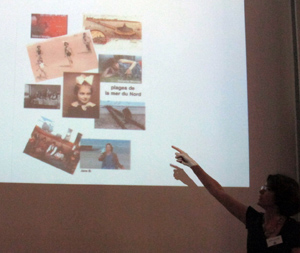

Other papers presented less institutionally fixed, more personal versions of screenwriting as a practice. Kelley Conway's lecture on Agnes Varda exploited unique access to the filmmaker's notebooks, scrapbooks, and databases. Kelley showed how Varda conceived three of her documentaries by means of strict categorical structures that were then frayed by digressions born out of the material she shot.

Anna Sofia Rossholm provided something similar for Bergman. Out of the vast Bergman archive she quarried sixty "workbooks," typically one for each film. Whereas Varda's books were filled with cutouts and images, Bergman was a word man, treating the books as diaries that recorded "this secret I." Anna Sofia proposed that in his jottings and planning, Bergman not only communed with himself (calling himself an idiot on occasion) but also explored patterns of doubling akin to those we find in the films. The workbooks evidently held a special place for him: he included their pages in films like Hour of the Wolf and Saraband.

David Lean might be thought of as working in between the Hollywood system and the more personal European milieu. Ian MacDonald suggested that one of Lean's unfilmed projects sheds light on what he calls screenplay poetics. MacDonald seeks, I think, a principled method for studying the creative process. He does this by tracing how a screen idea is transformed in a series of documents generated by the creative team. The process, he points out, is governed by the participants' various conceptual frameworks. For Nostromo, Lean solicited two screenwriters and oversaw their rather different versions of the novel. Ian showed that Lean seems to have found solutions to adapting the book by fitting it to the three-act structure advocated by Hollywood artisans, a concrete case of a filmmaker accepting a fresh "poetics" or set of creative constraints.

All of these inquiries could lead to more general thoughts about the creative process in cinema. For some filmmakers, it's a professional task, undertaken with full knowledge that problems and constraints will have to be dealt with. For others, such as Bergman and Varda, it's obviously deeply personal, even autobiographical. Perhaps most intimate was the film discussed by Hester Joyce. New Zealand filmmaker Gaylene Preston basedHome by Christmas (2010; above) partly on audiotape interviews with her father as he recalled his World War II experiences. Her script reconstructed her interviews with actors, then filled in scenes with documentary footage and scenes she imagined. It's a family memoir on several levels: Preston's daughter portrays her own grandmother.

The Screenplay: What Is It?

Several of these probes into the creative process raise a more theoretical question. How should we best conceive of the screenplay? As a blueprint? A recipe? An outline? These labels all suggest something disposable preliminary to the real thing, the movie. But why can't we think of the screenplay as a freestanding object? After all, there are films without screenplays, but there are also screenplays—some written by distinguished authors—that were never made into films. And some of these, like Pinter's Proust screenplay, are read for their own sake.

In cases like this, should we consider the screenplay a literary genre? And if the screenplay for an unproduced film can be considered a discrete object, what stops us from treating a filmed script in exactly the same way? Moreover, why even speak of a single screenplay, when we know that most commercial films at least go through several drafts? Can't we consider each one an independent literary text? We're now far from Carrière's idea that the script finds its consummation in the finished film and as a piece of writing it should wind up in the ashcan.

And not all screenplays are literary texts. The scrapbooks and databases that Varda accumulates are works of visual art, collages or mixed-media assemblages. Are these merely draft of the film, or do they have an independent existence or value? We seem to be asking the sort of question that Ted Nannicelli poses in his Ph. D. dissertation. Is there an ontology of the screenplay?

Take a concrete example. Ann Igelstrom's paper, "Narration in the Screenplay Text," asked how literary techniques are deployed in the screenplay. When a passage in the script for Before Sunset begins, "We see…," who exactly is this we? Ann argued that traditional narrative concepts involving the source of the narration, the implied author and implied reader, and the rhetoric of telling can illuminate conventions of screenwriting. Here the screenplay seems definitely a literary text.

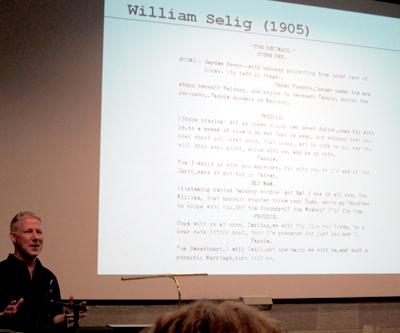

In his keynote address, "The Screenplay: An Accelerated Critical History," Steven Price (above) declared a more abstract interest in the ontology of the screenplay but proposed that there was no clear-cut way of defining it. Historically, the screenplay takes many forms. Steven pointed out that even in Hollywood, there were many alternative formats, ranging from detailed breakdowns to the "master-scene" method (the option that didn't specify shots or camera positions). And conceptually, the screenplay carried traces of its original production purposes, as well as other constellations of meaning. (Mack Sennett scripts seem to him part of a Sadean tradition of dehumanized, repetitive recombination.) So if there is a distinctive mode of being of the screenplay, outside of its role in production, it will turn out to be a messy one.

Envoi

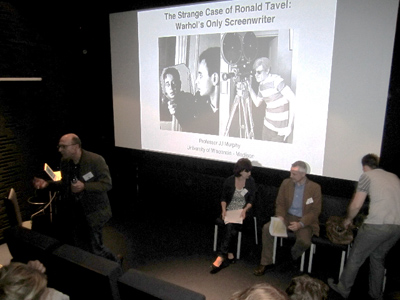

J. J. Murphy presents a paper on Ronald Tavel. Photo courtesy Richard Neupert.

If we conceive studies of screenplay and screenwriting as revolving around specific research questions, those of us interested in film as art can learn a lot. If our interests are in film history, researchers can show how organizations of production and individual choices by screenwriters/directors can shape the final product. For those of us interested in more theoretical explorations, asking about the nature and "mode of being" of the screenplay can't help but make us think more about the ontology of cinema itself.

And if want to know films more intimately, being aware of the creative choices that were made by the filmmakers throws a spotlight on aspects of the film we might otherwise not notice. It's all very well to say we'll examine the film "in itself," but our attention is invariably selective. Knowledge of behind-the-scenes decisions can sharpen our awareness of artistic matters. Anna Sofia's research on Bergman, like Marja-Ritta Koivumäki's paper on Tarkovsky's screenplay for My Name Is Ivan, activates parts of the film for special notice.

Because there were split sessions at the conference, and because I was plagued by jet lag, I couldn't attend every panel and talk. I regret missing papers I later heard were very fine, and I haven't written up everything I heard. I haven't sufficiently talked about screenwriting pedagogy, represented in papers like Lucien Georgescu's dramatic appeal to rethink whether screenwriting should be taught in film schools, or Debbie Danielpour's stimulating survey of her methods of teaching genre scripting. So this is just a small sample of what these folks are up to. But you can tell, I think, that they're posing questions at a level of sophistication that my 1960s cohort couldn't have envisioned. Despite what the cynics say, there is progress in academic work.

As for men's underpants: All is explained here.

I'm grateful to conference organizers Ronald Geerts and Hugo Vercauteren for inviting me to speak at the gathering. I must also thank conference organizer and old friend Muriel Andrin, along with Dominique Nasta and their colleagues and students from the Arts du Spectacle Department at the Université Libre de Bruxelles. My friends at the Cinematek, Stef and Bart and Hilde, helped me with my PowerPoint). Thanks as well to the Universitaire Associatie Brussel (Vrije Universiteit Brussel / Rits-Erasmushogeschool Brussel) and Associatie KULeuven (MAD-Faculty / Sint Lukas Brussel). A high point of the event was the visit to La Fleur en Papier Doré. Special thanks to Gabrielle Claes for her heartfelt introduction to my talk, not to mention a delicious bucket of moules.

A founding document in the contemporary study of the screenplay is Claudia Sternberg's Written for the Screen: The American Motion-Picture Screenplay as Text (Stauffenburg, 1997). Other books central to the conference cohort include Steven Maras's Screenwriting: History, Theory, and Practice, Steven Price's The Screenplay: Authorship, Theory and Criticism, J. J. Murphy's Me and You and Memento and Fargo: How Independent Screenplays Work, and Jill Nelmes's anthology Analysing the Screenplay, which includes many essays by members of the group. See also the affiliated Journal of Screenwriting. The next screenwriting conference will be held in Sydney, and the 2013 one will take place in Madison, Wisconsin.

Coke does go through you pretty fast. Richard Neupert at a Coca-Cola machine that exploits a Brussels landmark.

JCC | David Bordwell

The Milky Way (La Voie lactée, 1969)

DB here, writing from a gray Brussels:

All the problems of a film are in the script.

When a film is made, the screenplay disappears.

When you consider what a scene needs to express, ask: How can the actor act it?

When you're writing a scene, try to act it out yourself.

Rather than letting dialogue explain the action, let the action explain the dialogue.

It will always be possible to make films. Don't forget to make cinema.

These and other epigrammatic insights flowed easily from Jean-Claude Carrière during his visit to the Cinematekof Belgium and the annual conference of the Screenwriting Research Network. I hope to devote a later blog to other attractions of this stimulating get-together. For now, a brief tribute to the volcanic charm of the legend known as JCC.

JCC entered cinema under the aegis of Jacques Tati. Tati wanted someone to turn M. Hulot's Holiday and Mon Oncle into novels, and the very young writer seemed the right candidate. But Tati quickly learned that JCC didn't know how a film was made. So he assigned Pierre Etaix and the editor Suzan Baron to tutor the lad in the ways of cinema. First lesson: Go through M. Hulot on a flatbed viewer, examining the script line by line while watching shot by shot. As a result, JCC says, he began to understand "the film that you don't see."

In the course of his career, JCC has written novels, plays, essays, screenplays, even a scenario for a graphic novel. In the process he became one of the most distinguished and respected screenwriters of the last fifty years. His most famous collaborations were probably with Buñuel, from Belle de Jour (1967) to the master's last film, That Obscure Object of Desire (1977). He worked with Etaix (The Suitor, 1962), Forman (Taking Off, 1971), Schlöndorff (The Tin Drum, 1979), Godard (Every Man for Himself, 1980), Wajda (Danton, 1983), Oshima (Max mon amour, 1986), Kaufman (The Unbearable Lightness of Being, 1988), Peter Brook (The Mahabarata, 1989), Malle (Milou en Mai, 1990), and Haneke (The White Ribbon, 2007). He has also become known for his work on major French costume pictures and adaptations, such as Cyrano de Bergerac (1990) and The Horseman on the Roof (1995), as well as work with younger directors, including Wayne Wang (Chinese Box, 1997) and Jonathan Glazer (Birth, 2005). His TV scripts are numberless.

Directors both young and old come to him for the unique forms of collaboration that he offers. Instead of going off to write the screenplay, JCC meets frequently with the director. (Sometimes the director stays in his house.) He might ask the director to write the script for him, and they go over the result. Through these methods, JCC tries to help the director "find the film that he wants to make." But his methods are flexible, tailored to the director's temperament. When he was working with Buñuel, the men met daily to tell each other their dreams, some of which wound up in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972). Similarly, JCC prefers to meet with the actors before production, letting them try out the parts so that he can revise things for each one's habits of speaking. For Cyrano, Depardieu read the entire play aloud, taking all the parts, and then listened to it over and over on cassettes to refine his interpretation.

Brussels gave JCC a busy twenty-four hours. In conversation with the critic Louis Danvers he introduced a Cinematek screening of The Milky Way. He gave a keynote address for the Screenplay Network conference, and he participated in a panel discussion with members of the Flemish Screenwriters Guild at the film school RITS. These sessions ranged freely over his career and his conceptions of filmmaking. He believes that there is a language of film that sets it apart from other arts. That language is grounded in the play of meaning and emotion that comes from putting one shot after another.

He explained the point through an example that seems at first to be a restatement of the classic Kuleshov effect. In Shot 1, a man in his apartment looks out the window. Shot 2: The street. A woman is walking with another man. We'll assume that our man is seeing them. Shot 3: Our man reacts.

But contrary to Kuleshov's dictum, his facial expression should not be neutral. In fact, his expression tells us how to understand the scene. If the man looks upset, we surmise that he's jealous. If he's benevolent, we assume that the woman is a friend, his daughter—or a flirt. The filmmaker needs not only techniques like framing and cutting, but also the performances of actors.

Now cut to the woman in her bedroom brushing her hair. We need to make sure the audience understands that it's the same woman, so maybe we have to go back and add a shot to the earlier scene, a closer view of her in the street. This constant flow and readjustment of images is based on guiding the spectator discreetly but firmly through the action. The audience isn't aware of this "secret film," but it governs everything the viewer thinks and feels.

For this reason, the young screenwriter needs to learn everything about how a film is made. When JCC was acting in The Wedding Ring (1971), a film starring Anna Karina, he learned that simply getting up from a couch can be a complicated matter. When he stood up spontaneously, dipping forward to lift his body, the cinematographer had to correct him: It looked awkward on film. JCC learned that he had to stand up in an unnatural way, with his feet spaced and his back rigid, so that it looked smooth on film. The screenwriter must know that even the smallest moment of action, easy to write in the comfort of a study or a café, is subject to the contingencies of production.

For this reason, the young screenwriter needs to learn everything about how a film is made. When JCC was acting in The Wedding Ring (1971), a film starring Anna Karina, he learned that simply getting up from a couch can be a complicated matter. When he stood up spontaneously, dipping forward to lift his body, the cinematographer had to correct him: It looked awkward on film. JCC learned that he had to stand up in an unnatural way, with his feet spaced and his back rigid, so that it looked smooth on film. The screenwriter must know that even the smallest moment of action, easy to write in the comfort of a study or a café, is subject to the contingencies of production.

Where to get ideas for films? From the classics, of course. ("Balzac is the greatest screenwriter—every character is vivid.") But above all you must observe reality. Tati taught JCC to sit vigilantly in a café. Study everyone who passes. Notice details. Imagine the person as a character in a story. Give him or her some motivations. What you must do is "find the fiction in the reality." When JCC presided over the French film school La FEMIS, he promoted an exercise that required students to move out into a public space, like a market, and come back with stories about the people they saw. JCC praised Tati's genius for spinning gags and situations out of passing life—"as if God had created the world so that it could furnish a film by Jacques Tati."

JCC must be one of the few screenwriters who doesn't gripe about his work being changed in its final incarnation onscreen. He sees the screenplay as ephemeral, the chrysalis for the butterfly. Once you accept the fact that your text must be sloughed off on its way to becoming cinema, you can take joy in your work. For young people, JCC advised the same relaxed, exploratory attitude. Conceive of yourself as a writer, able to move across media. The venues for your writing are constantly changing, so be prepared to write for television as well as film, to write comics and documentaries and plays. Above all, "Don't despair of the future of cinema. It's wide open."

Jean-Claude Carrière turns eighty next week.

The best introduction to Carrière's career and ideas that I know is his book The Secret Language of Film (Faber, 1995). Some of this text overlaps with Exercice du scénario (FEMIS, 1990), coauthored with Pascal Bonitzer. That book is worth reading too, but it hasn't to my knowledge found English translation. An illuminating interview is here.

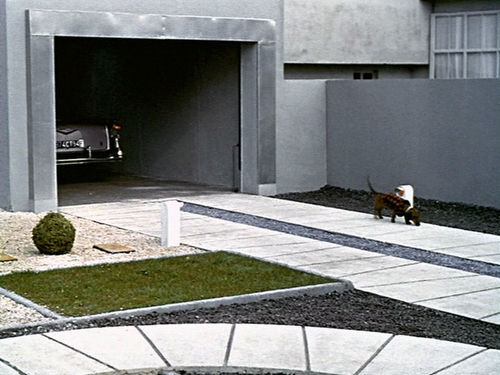

Mon Oncle (1958). "I followed Tati more or less everywhere, usually with Etaix, attending projections followed by long anxious discussions. ('Can we clearly see the dog's tail go past the electric eye that shuts the garage door? Yes? Clearly? You're sure people will see it?')

P.S. 11 September 2011: Thanks to Jonathan Rosenbaum for correcting an error in JCC's filmography, which I've rectified above. Jonathan also remarks:

I assume that you know, by the way, that Carrière appears in a scene of Certified Copy, playing something similar to the "wise old guru" role played by the Turkish taxidermist in Taste of Cherry and the doctor in The Wind Will Carry Us.

I did know and should have worked it in!

Wednesday, September 14, 2011

Another Rare Terrence Malick Interview (1974) - All Things Shining

FirstShowing.Net on the interview:

The interview itself focuses on the filming of Badlands - Malick's 1973 directorial debut, which he also wrote, starring Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek in a "dramatization of the Starkweather-Fugate killing spree of the 1950's, in which a teenage girl and her twenty-something boyfriend slaughtered her entire family and several others in the Dakota badlands."

The quick-fire Q&A between the writer/director and G. Richardson Cook (the interviewer who also happened to be a Production Assistant on Badlands) is a fascinating conversation about making an independent feature outside of the studio system and without a distributor in place at the time of production in an era of Hollywood during the '60s and '70s where this type of filmmaking was still kind of emerging and evolving (in comparison to modern independent filmmaking at least). So much was different and yet so much was the same (for example, approaching dentists and lawyers for funding and lying about your production costs).

In response to Cook's question "How was Badlands financed?" Malick said "It was financed like a Broadway play - that is on a limited partnership arrangement with a lot of investors who didn't know one another each coming in for a small piece, anywhere from $1000 to $50,000." (the budget onBadlands was supposedly "under half a million dollars" though Malick reveals he had been advised to say that.)

If you're an independent filmmaker yourself, a fan of Malick's work, or just a film lover in general, this vintage gem is a must read for sure.

http://www.firstshowing.net/2011/rare-interview-with-terrence-malick-from-1974-filmmakers-newsletter

Monday, September 5, 2011

The Fate of Documentary Film | Leslie Stonebraker

Traditionally, the festival circuit is the funnel to theatrical distribution. But like a funnel, this method enables only a fated few to make it to the marquees. The Internet offers a direct pipeline to viewers without relying on the mercy of big time distributors and movie houses. The complete democratization of technology, coupled with the prevalence of YouTube and its analogues, provides filmmakers a ready way to self-distribute their films.

"Obviously, the Internet will help," Battle for Brooklyn director David Beilinson clarifies. "But the problem is that the filmmakers don't get paid. The main thing is to figure out how to get filmmakers money so that they can continue to make films and still make them available."

The conundrum is clear: It is easier than ever to make a good documentary film, but just as hard to reach an audience in a way that makes a profit. How can a filmmaker make it in this post-millennial environment?

"The web isn't really a destination. The web is millions and millions of destinations. Even something as successful as Netflix and their recommendation engine, it's still not easy to build an audience for a documentary." Sehring strongly believes that only sites of consumption that are a destination—theaters, television or VOD—can offer indie filmmakers a taste of commercial success.

But this relationship will not result in a huge marketing campaign. Sehring admits that in a documentary, "we look for something that will appeal to an audience that has a core following anyway." In this ideal scenario, "you can do a lot of grassroots marketing" for the film, rather than spending the big bucks on promotional material to attract a new following.

Gideon Lichfield, curator of the Economist Film Project on PBS, agrees. "You have to be good at everything," he explains. "It's no longer just about the film itself, it's about the whole process that goes into the making of it, the funding of it, the distribution of it and the promotion of it, because as a filmmaker you have to do all of those things probably to a greater extent than you used to."

While Shimkin acknowledges that the Internet is the future, he still believes in what he calls "the collective viewing experience." Something about a dark room and a rapt crowd makes a movie worthwhile. For this reason, prior to monetizing a film via the Internet, Shimkin would "like to think that there's still a place for them in the theatrical setting."

It all seems to come down to marketing. Unbidden, almost every person I spoke to for this article brought up self-marketing as the primary factor behind the success of a documentary film. It is only a blessed few films that can make it through mainstream channels and specials like PBS' POV Series or OWN Network's new Film Club.

Even if funding is secured, the film is well made and people would be interested in seeing it, it may just come down to luck.

Andy Schupak, a partner in streaming website Festival-of-Films, agrees. "In the old days, you probably had a market to reach the distributor, but today you're going directly to the end user. So you have to figure out how to market to them."

The democratization of technology means that quite suddenly, truly amazing documentary films can be made for the price of a used car. Hollywood's exclusive ownership of filmmaking infrastructure is crumbling. Like in the pivotal technological transitions that have come before, the fate of documentary film will ultimately rest in the eyes of the viewers. Unfortunately, right now many films are getting lost between production to consumption. It is uncertain what the future of distribution—web and otherwise—will bring for documentary filmmakers, but one thing is clear: documentary will still survive.

Sunday, September 4, 2011

DSLR filmmaking: fad or the future of cinema? | Fotorater - Robert Francis Taylor

The rise of DSLRs has caught the attention of professional filmmakers – but are they a game-changer or a distraction for those who strive for success in the film industry?

If you had spoken to professional cinematographers and filmmakers five years ago and told them that the next breakthrough for guerilla filmmaking was to come from a stills camera, they would have thought you were mad. Flash-forward to the present day, and that is exactly what has happened.

The advent of filmmaking with DSLRs has sprung up and surprised many people with its relatively low-cost but high-end results, giving practically anybody the chance to create eye-catching cinema.

The reason DSLRs have attracted so much attention is because of the sheer quality that they can deliver, despite not coming with the huge price-tag of a traditional film camera. It's no surprise that cinephiles and industry professionals are starting to sit up and take notice, with this mode of filmmaking even capturing the attention of Darren Aronofsky, who used a Canon 7D and Canon 1D Mk IV to film particular sections of his award-winning film, Black Swan.

It's not just because of the quality footage that DSLRs can deliver, but also down to the practicality of these tiny cameras. Traditional films would have to be shot and then processed before any editing could be done. This was a very lengthy and expensive process that has been made cheaper and quicker with a digital workflow that digital filmmaking brings with it. It's these advantages that allowed the season seven finale of US TV show House to be shot entirely in only 10 days with a Canon 5D Mk II (pictured). Having shot various projects myself using various cameras, I can attest to the super-practical nature of these cameras.

Similar to the introduction of the home-video camera to the masses in the 1980s, the DSLR revolution has allowed non-filmmakers access to high-end equipment. Coupled with the rise of YouTube, budding film-makers now have a product and a means of distribution that was unprecedented. But is this a good thing?

At one end of the spectrum are those with little technical or storytelling ability, who upload countless numbers of dreadful videos that saturate the number of online films with genuine talent behind them. And then there are those at the other end who now find themselves in an ever more competitive market where visual aesthetics are not something to fall back on, but are regarded as being necessary.

The ability, or lack thereof, to capture any decent quality of sound with these cameras is also a huge issue. Pioneers of the DSLR movement like Philip Bloom spend a great deal of their time investigating and reviewing the best ways of enhancing DSLR filmmaking, but these workarounds are not entirely cheap and this is where the future of DSLR shooting starts to get interesting with Canon and Sony developing improvements.

Although I've expressed some qualms with the open access that these cameras have given to the market, the drawbacks might put many amateurs off. After the initial cost of the camera and then a decent lens, there are dozens of add-ons and extras that only serious filmmakers will consider buying. The focus now, more than ever, will be on great storytelling. You can shoot hilarious videos of your friends messing about with a shallow depth-of-field, but once people realise that your 'story' is just as shallow, they'll soon log off. With new camera models from Canon and Sony being developed, the future of DSLR filmmaking is looking very bright for the next generation of storytellers.

DSLR filmmaking: fad or the future of cinema? | Fotorater - Robert Francis Taylor